|

|

||||||

|

|

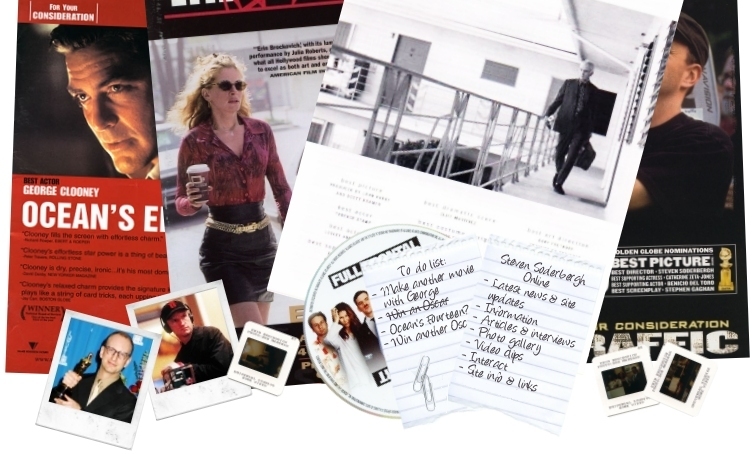

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

Soderbergh Brings Past, Present Together in The Limey Director Steven Soderbergh is not new to gritty realism. But his newest film, The Limey, represents a change in tone from his recent work - the polished action film Out of Sight and the comedy Gray’s Anatomy. The Limey tells the story of a reformed Cockney thief from London who is searching for an explanation to his daughter's untimely death in Los Angeles. The film plays on cultural conflicts as it jumps from present to past in a non-linear story line. Central to the film's tone was the strategic casting of the two Oscar-nominated actors - Terrence Stamp and Peter Fonda - because in may ways The Limey mirrors key roles each actor performed in the past. Not only does Soderbergh's casting of the film support the character-driven piece, Stamp’s '60s persona impacts his role directly. Creating a unique storytelling device, Soderbergh acquired the rights to Ken Loach's 1967 film Poor Cow, in which Stamp portrayed a young British thief named Wilson (the same name of his character in The Limey). Through editing techniques, Soderbergh places images of Stamp from Poor Cow into The Limey, where the actor plays against himself 30 years ago, allowing the director to illustrate the character's introspection. Steven Soderbergh shook the international film community when he won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1989 with sex, lies, and videotape at the age of 26. Since then he’s directed seven films and is currently working on two new features: Erin Brockovich, a story about a research assistant up against a large utility company blamed for causing an outbreak of cancer, and Traffik, a drama about the world of drug trafficking. This is a departure from your recent films. Did you make a conscious effort as a filmmaker to try a different style? Well, it's conscious in that I tend to be a bit restless, and try to find things that will provide a different experience than the film I've just finished. I tend to keep looking for things that I haven't done before. I've made three non-linear crime films in the past year. Each of them had different concerns. So I felt at least I wasn't completely repeating myself. How comfortable are you working in the thriller genre? I'm very comfortable. But I don't know why that's the case because I didn't grow up with an overriding interest in that genre. I liked it, but I wasn't obsessed with it. I grew up in a suburban subdivision, so it wasn't anything that touched me personally. But I guess I found that it's a resilient genre, and it - almost more than any other genre - allows you to inject your own preoccupations onto it. It sort of meets you halfway. And you have all these very solid pillars to build something around. I guess that is its appeal for filmmakers. Your decision to cast Stamp and then to use him as he was 30 years ago is a lovely touch. How did that decision come about, and were you aware of a precedent in filmmaking for such a device? The only film I can think of is at the beginning of The Shootist, which starred John Wayne. There was a brief montage of him supposedly in character as a younger man. But as far as using an actual character from another film, and having it play a role in the plot, that I don't know. The writer and I couldn't come up with an analogy, but that's not to say it hasn't happened. It's going to get more and more difficult to happen because these days, negotiating the rights to do something like that is very difficult. It took us a long time. I didn't get the rights cleared until we were well into post-production, which was terrifying. Was it up to Ken Loach at all? No. It was strictly that the rights were held by two different companies, so it took a long time to figure out. But it came about because once Lem Dobbs, the writer, and I settled on Terence as the person we wanted to build the movie around, I said, "Well, gosh, it would be great if we could get some footage of him from the '60s.” And Lem said, "Well, there's this Ken Loach film, Poor Cow, where he plays a young thief." And I had never seen the film, because it's not available here. But Lem had a sort of fifth-generation bootleg sent over, and I looked at it and thought, "It's perfect." There is more than Stamp linking you to Loach - there are similarities in style and tone to his work. Did you draw inspiration from his film for the The Limey? With the exception of Poor Cow, I was reasonably familiar with Loach's work. I did go back and look at a lot of it again. I also looked at a lot of things even a third and fourth time for the film that we're finishing now, Erin Brockovich, which is a ground-level biopic of sorts, but whose style I wanted to be very simple and not slick. And so I watched a lot of the Loach films again to determine how he was staging things and how he was shooting them to give them a feeling of having been captured instead of staged. It was very helpful. And I finally got to meet him, which was great. In your pursuit of realism in The Limey did you travel to East London to learn about cockneys? Or did you simply trust Stamp to bring that kind of authenticity to the film? A little of both. Luckily, I've spent some time in those areas of London. I'm certainly familiar with what has come out of that area culturally, whether it be films or television or music. All that is reasonably familiar to me. And then, Lem grew up there, not as an East Ender, but was very familiar with that territory. I had long talks with Terence about what it was like to grow up there, and the people that he knows, still knows, and knew, who had with those kinds of lives. He said if you grew up in that area, there's a point at which you have to determine which side of the law you're going up end up on. And he said, "I know a lot of guys who ended up on the wrong side and went to prison for long stretches of time." We had a lot of talks about what that kind of person his character is like. It would have been different if I were shooting it there, it would have been a much more intensive research project. But since the whole idea was about a guy landing in Los Angeles, I think for my part, it was more about character than the location he came from. How did Stamp react to the idea of playing against himself 30 years on? He seemed to be very excited about it, which is unusual. I don't know that I would be, or any of us would be. But he was intrigued by it. He said at the time, "I'm not sure anybody's ever done it this way before, and I'm really excited by that, because I like doing things that are different." Given his characteristic personality and speech did you have any concerns about the language and how it might come across on film in the United States? No, not really. I guess I felt that the context was pretty clear, and that a literal understanding of everything he said wasn't really relevant and in fact might be part of the point of the film. Was the monologue he delivers to the police detective scripted? Yeah, that was scripted to the syllable. Those kinds of things have to be when you're trying move as quickly as we're moving, with actors who are as prepared as Terence. It's a funny little speech. You've edited a number of your own films. How hands-on were you in the editing room with Sarah Flack? Editing is a very intensive and collaborative period. It's where the film is finally being made, in a way. And in this case, there was a lot of experimentation. Some of our early versions went too far and resulted in something that was almost incoherent to people who had worked on the film. And we ended up backing off a little bit, and finding a better balance between the sort of abstract impressionistic side of the movie and the straightforward narrative side. That just required a bit of trial and error. That's normal, but there was more in this film than a lot of other films I've made. But editing was really fun. One of the reasons I wanted to make the film in the first place was that there were some narrative ideas that had occurred to me during Out of Sight that I didn't get to try. I was looking around for something that would allow me to explore some of these ideas because I didn't feel I was finished with them yet. And this was a good opportunity. Which particular sequences or moments in the film are you referring to? There are a couple of what I call the interior-of-Wilson's-head montages that would fall into that. It's just about trying to come up with a different way of supplying information to the audience and seeing if they were open to that. We skip around and go into passages of stream-of-consciousness, which is something you can do very easily in writing but which people don't do as often in films. I just felt there had to be a more interesting way to provide exposition than just laying it out in a sort of A-B-C fashion. It's not appropriate to do that for everything. But I thought the spine of this film was so straight that I could afford to digress, because the audience would always be very clear on what the movie was about. They know it's a guy who shows up trying to find out what happens to his daughter, and that's all the movie is, so no matter how abstract I get, they always know it's going to come back to that, because that's what the movie is about. And if the premise had been as complicated as the style, it might have been impossible for people to put together. So I purposely chose something that I thought was very simple. An interesting device you use is the way the natural sound cuts off in certain climactic moments and the music takes over. Well, that stuff has all been done. When you're dealing with a film that's basically a memory piece and allows you to not always have to adhere to the literal interpretation of events, then you begin to think more along those lines. In one specific scene, where Terence and Lesley Ann Warren are about to be ambushed by two hit men, my supervising sound editor said, "You know, I don't think the scene is having quite the effect that it should have, because it's so literal," the way it was. He put together a very quiet sonic wash to put over it that suggested that after the gunshot, we go into this little aural audio landscape and not come back until the following scene. When we looked at it, I thought, "Oh, well, that's much better." And that's because all of us were thinking that way. You know, just as sometimes people on screen will be speaking and then we'll cut to a tighter shot of them, and they're not speaking right in the middle of a sentence. We had the license to abstract anything we wanted to. It's always nice when you work with people who come up with those suggestions because they are not paying attention to what is going on. Was the process of testing the film part of The Limey as well? In this case, the only screenings I had were for friends. I had called Artisan and said that in my opinion, we would be throwing our money away to do formal previews on this movie, because it's never going to score very well. It's the type of film that will not benefit from having these screenings. What I preferred to do was screen it for the most intelligent group of friends I could put together, and get ideas that way. They agreed. So I did just three or four screenings where I invited a different group of friends each time. It was writers, directors, actors, some other friends who are not in the film business, people who are reasonably intelligent and have a relationship with me that allows them to speak very frankly. Sometimes it would be brand-new people, and sometimes it would be people who had seen it before, so I could get a balance of opinions from people who were watching the film change. I think in this case, that was a good thing to do. Ann-Margret is given a credit but doesn't appear in the final film. What is the story behind her involvement? She had a scene as Peter Fonda's ex-wife when he shows up at the house in Big Sur. It was a scene that culminated in a lengthy monologue that I really liked, that I had asked Lem to write. I remember one day, I told him I had recently seen Network. And I said, "Gosh, you know, people used to have monologues in movies. I don't feel like they have monologues any more." And Lem wrote this scene with Peter Fonda's ex-wife doing a lengthy tirade about Peter and his lifestyle. And it all turned out very well. The problem is it had to be all or nothing. It was an eight-minute sequence. If it's Ann-Margret, you can't just have it be a minute. I decided, based on the rhythm of the movie and my sense that Peter's character didn't really need much more backstory than it had, that I just had to pull the whole thing out. That was a difficult call to make. But I felt that an eight-minute sequence right there really brought the film to a halt. And I decided to keep it going. What is the project you are about to go into production for Fox 2000? It's loosely based on a miniseries from the United Kingdom that was on about 12 years ago, I think. It's about drugs. It's a top-to-bottom look at the current state of the alleged drug war, all the way from how policy's made to how drugs get to a street corner in Kentucky. And there are three story lines that interlock, playing out simultaneously. I'm excited about it. The subject is interesting to me, and I've never had a narrative that allowed for this much cross-cutting, which I think is really fun, and can result in a really exciting movie. So I'm pretty jazzed about it.

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||