|

|

||||||

|

|

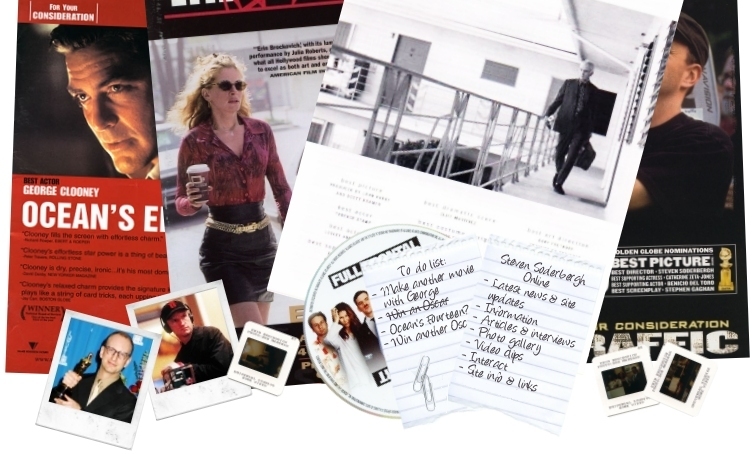

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

Emotion, Truth and Celluloid In 1995, Steven Soderbergh had reached a career dead end, just six years after igniting the independent-film craze with his debut film, sex, lies and videotape - a movie he recently (and correctly) characterized for the British film mag Sight and Sound as "a modest piece with modest aspirations that happened to be what people wanted to see in a way I obviously haven't been able to duplicate." His pastiche Kafka (1991) and Depression-childhood saga King of the Hill (1993) didn't spark with audiences or generate critical or cult followings. He simply floundered in his flop '95 neo-noir The Underneath, smothering snappy lines and arresting arcs of character with arty coups de cinema. But in 1998, he came up with Out of Sight, a smart, engaging action comedy about the love that ignites between a bank robber (George Clooney) and a deputy federal marshal (Jennifer Lopez) when she stumbles into his jailbreak and gets to know him in the trunk of a getaway car. It won best picture of the year from the National Society of Film Critics, beating out favorites like Shakespeare in Love and Saving Private Ryan. (The group also named Soderbergh, not Spielberg, best director.) And Soderbergh's The Limey, which opened last fall and ranks high on many a 10-best list, is an unexpectedly touching act of hard-boiled cinematic seduction. It tells the story of a canny British ex-con (Terence Stamp) who flies to L.A. to exact revenge on the man who killed his daughter. Soderbergh puts this basic thriller setup into a time-hopping form that resembles an elaborate paper cutout - the kind that comes all raveled up and reveals its true meaning when the last piece is uncovered. Like Out of Sight, The Limey is a light movie, not a superficial one. Soderbergh has learned that an audience will follow any director to what lies underneath as long as he keeps his film expressive on the surface. History and current events meld in the ex-con's brain, as he thinks back on his daughter and her mother. But Soderbergh does more than play memory games with fleet flash-forwards and flashbacks. At the end we realize that the entire film has been the gangster remembering things past and judging his own culpability.

The Limey is a salute to 1967 filmmaking: It echoes John Boorman's

Point Blank and actually uses footage of Stamp playing a young

thief in Kenneth Loach's Poor Cow. So it's wonderfully appropriate

that Soderbergh has come forth with a book on filmmaker Richard Lester,

who by 1967 had already made A Hard Day’s Night, Help! and the

audacious How I Won the War. In addition to his penetrating interviews with Lester, Soderbergh sandwiches in the candid journal of a chaotic year in his own career - 1996, right after The Underneath and right before he landed the directing job on Out of Sight. He was finishing up two idiosyncratic, small films, Schizopolis and Gray's Anatomy, while doing script work for hire, staging Jonathan Reynolds' play Geniuses, helping to produce Pleasantville and struggling to mount an adaptation of A Confederacy of Dunces. What's neat about Getting Away With It is that you witness Soderbergh renewing himself as he talks to Lester. The younger director opens up to the older one, who delves into matters as different as evolutionary theory and military milestones. Even the structure of the book expresses Soderbergh's burgeoning energy: It's a delicious parody of the exhaustive, multi-part director interview - a specialty of Soderbergh's own publisher, Faber and Faber. ("ff" usually does bring their books into this country, but this volume is available right now via Amazon.co.uk and other British-book delivery services.) Soderbergh's readers were the first in their arthouse or multiplex to hear the name of Being John Malkovich screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. In 1996 Soderbergh had tried to launch another Kaufman script, Human Nature. The director's readers were also the first to learn of "tortious interference," the legal concept at the center of Michael Mann's The Insider: Paramount invoked it to prevent Soderbergh and his Limey producer Scott Kramer from setting up A Confederacy of Dunces as a co-venture with other companies. Most important, the book delivers a privileged glimpse into the sensibilities of filmmakers who use sophisticated film syntax to heighten emotion and find novel ways of embodying old storytelling values of romance, suspense and catharsis. When I phoned Soderbergh in L.A. in December, he was taking a pause from

his forthcoming feature Erin Brockovich (due out in March). He

instantly made clear that Lester isn't his only idol. He said that Erin

Brockovich, a socially conscious character study starring Julia

Roberts, fit "the John Huston plan for career longevity: Never become too

hip or faddish."

That's unfortunate, because it has a lot of topical hooks, including

the first mention between book covers of screenwriter Charlie Kaufman.

Your comment on his Human Nature script - you call it indescribable

except for being "very weird" and "hysterically funny" - hits home for

anyone who's seen Being John Malkovich. He's probably, in the long run, pretty smart to do that. I still have fantasies myself of pulling a Terrence Malick. It's really a silly problem, but it's frustrating to be in a situation where you become bored with speaking about what you love to do for a living. You find yourself hating not just the sound of your voice, but hearing it make the work that you do sound boring. It's a terrible sensation. You definitely get to a point where you feel like a homeless person babbling on a corner, saying the same thing over and over to very little effect. In the long run I don't know how much good talking does. I don't think audiences pay too much attention - people who want to go to a movie will go. When you look at the selling part of the business, everything that everybody does for every movie feels the same. We did a ton of press for The Limey. Maybe it would have done even worse if we hadn't, but I can't say what helped and what didn't.

The Limey is loved by the people I know who've seen it; I'm

surprised to hear you say it didn't do well.

Much of your book is about trying to maintain enthusiasm and energy

over the course of a career. There's a wonderful interplay between you and

Lester - almost as if you started the book out of devotion to his movies

but then had these revelations about your own films. When I see people who I think have become either cynical artistically or just competitive to the point of self-destruction, what they share is the loss of appreciation for anything that anybody else is doing. Seeing something good should make you want to do something good; if you're not careful, you can lose that. And that can hurt you. I still get a charge out of seeing a really good movie or reading a really good book or watching The Sopranos on TV. Working my way through Lester's films, and doing these interviews with him, I was reinvigorating myself. And there was also something cautionary about it. Lester did stop working for a variety of reasons. So for me there is the element, whether it's spoken or not, of "Wow, will that happen to me? And to all of us?"

There are recurring topics and themes in the book. You talk a lot about

one of Lester's favorite actors, Roy Kinnear, who died after he fell from

a horse during the making of Lester's last film, The Return of the

Musketeers. You touch on whether Lester's atheism made him feel more

responsible for the accident than he would have if he'd believed in a

divine plan, and hastened his departure from filmmaking. It makes the

reader confront the moviemaker as a person, not a technician.

And then you have all these self-deprecating footnotes, which touch on

comic battles with your editors at Faber and Faber. You have a jokey "Note

From Your Publisher" and two mock author's notes, including an outline for

an introduction that will contain an "Awesome display of ego disguised as

humility; joke about same." Even the title and the cover design make your

book feel as irreverent as a Lester movie. I mean, I love all the director books they do, "So-and-so on so-and-so"; I've got all of them. But I thought, “We've got to tart this up a bit. We've got to put on some bells and whistles, so if somebody picks it up off the shelf they'll feel they have to buy it.”

A lot of younger directors, as different as Danny Boyle (Trainspotting)

and Stacy Cochran (My New Gun) and Michael Patrick Jann (Drop

Dead Gorgeous), have taken inspiration from Lester's movies.

Usually, when you talk about a director of ideas, you think of someone

cerebral or self-conscious. But Lester at his best is downright blithe

about getting his ideas to the screen. Because Out

of Sight and The Limey have such stylistic confidence, it's odd

to think of them as in any way "tossed-off." What you call relying on

instinct must also mean relying on whatever craftsmanlike reflexes you've

built up. But as we both know, a lot of people aren't paying attention. Directing has become the best entry-level job in show business. You have to keep your eye on the long term - which is why I understand what Charlie Kaufman is doing. I try to be careful about things I do and not promote myself separately apart from a film I'm talking about. I've never taken a possessory credit, because anything that furthers the idea of you as a brand name is risky - because people get tired of certain brands.

Lester is frank about decisions he made that have sometimes been called

forced and inorganic. For example, he admits that he conceived the

elaborate structure of Petulia because he was afraid that if he

didn't it might have come off as "a romantic novelette."

Out of Sight is juicy - just as ambitious stylistically, but

with emotional coherence and impact. When I first saw the opening flourish

of George Clooney ripping off his tie and the jacket of his suit, I was

happy to accept it as an expression of anger and frustration, without

knowing whether it would fit into the rest of the movie. As for The Limey: That is about a guy who cannot stay rooted in the present. He is completely dislocated.

From the start, the cutting in The Limey conveys the play of

thought and memory, but I wasn't prepared for the cumulative effect. The

whole movie hinges on a speech and a gesture that the daughter of the

antihero (Terence Stamp) makes to him as a little girl and to the villain

(Peter Fonda) as a woman. Via flashbacks, a woman who is dead carries the

film's emotional weight - and turns it from revenge film to tragedy. Looking back at the movies we were riffing on, Point Blank and Get Carter, I realized that I love those movies but they're not the most emotional experiences in the world. They're very compelling and they're pretty cold. And I thought that if we were going to do one of those movies, we needed to have a strong emotional undercurrent. When you see most shoot'em-up revenge movies you don't get too emotionally invested. The combination of how we thought about it and casting Terence and finding that footage from Poor Cow helped build the quiet emotional foundation that pays off in the end. When

Lester was in his prime, he would get an idea and get a writer and just go

off and do it. Are you able to operate the same way? Would you want to?

All I know is that it's based on a real-life story about a woman (Julia

Roberts) involved in researching a health-related lawsuit against a

utility company. It sounds like A Civil Action. There's one courtroom scene halfway through the film that's two minutes long. I just found her character fascinating. And the story was so aggressively linear that it required a completely different set of disciplines than The Limey or Out of Sight. I had to be a different filmmaker to do what I thought was appropriate for telling it. There are movies where you can get away with a certain amount of standing between the screen and the audience and waving your hands. This isn't one of them. You need an understanding of when you need to let things play and not be intrusive. At the same time, I hope you'll absolutely recognize Erin Brockovich as something that I've done, because there is an aesthetic at play that relates it to films I've made before. And it does have a protagonist who is at odds with the surroundings; I tend to be drawn to those. Here it happens to be a lower-income woman. It was fun to make a movie where the protagonist was female and was in every scene of the film. If you're a certain kind of filmmaker, everything is personal, whether a movie is about yourself or not. But I think, for the most part, people who write about film have a very limited idea of what personal expression is and how it can manifest itself. As a result you often find directors being encouraged to make "personal films" when they would probably grow faster and go further if they began to look outside of themselves. That was the real turning point for me: I wasn't interested in making films about me anymore, and my take on things. I thought, "I've got to get out of the house!" And I've had more fun and I think the work is better since that occurred to me. I'm interested in other people's experiences - filtered through mine, obviously. I'm absolutely as connected to Erin Brockovich emotionally as I was to sex, lies. Some people just either can't believe that, or don't want to believe it, or just don't understand the process. You don't spend a year and half on something you don't give a shit about. There's

a great passage in the book where you ponder an American director's

alternatives: "…make stupid Hollywood movies? Or fake highbrow movies with

people who would be as cynical about hiring me to make a 'smart' movie as

others are when they hire the latest hot action director to make some

blastfest?"

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||