|

|

||||||

|

|

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

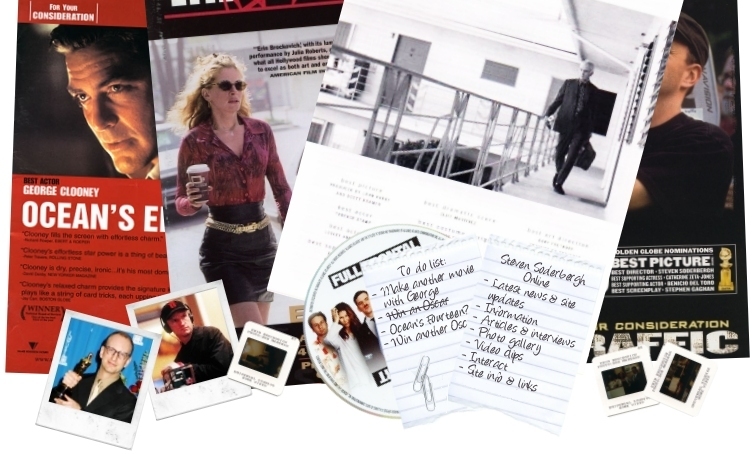

Whatever happened to Steven Soderbergh?

"I guess I'm stuck in a timewarp," mutters Steven Soderbergh with what sounds like bemused resignation from the other end of a transatlantic phoneline. "Twenty years ago, I would have been in the mainstream. Twenty years ago, films like 'Carnal Knowledge' and 'The Last Picture Show' were mainstream. Cinema was more sophisticated. People were more accustomed to challenging experiences than they are now." And Steven Soderbergh, more than most, is a man who knows a fair bit about challenging experiences. In the four years since his debut feature sex, lies, and videotape brought him worldwide acclaim and the Palme d'Or at Cannes, the writer-director has seen himself develop from bright-young-thing-most likely-to into a 30-year-old whose name now regularly appears in close proximity to the familiar words "whatever", "happened" and "to". So what exactly did happen? "I was offered the whole gamut of stuff from very big studio things to films exactly like sex, lies," he recalls. "I think that Hollywood saw me as a commodity, someone it would be good cocktail conversation to have attached to something. But I knew what I wanted to do, so I set up those projects and got the hell out." The first of these projects was Kafka, an arty, black-and-white Expressionist thriller starring Jeremy Irons, mixing elements from the bizarre life and esoterc works of the eponymous Czech writer. "It was a film," enthuses Soderbergh, "that only a stupid young man could make, or would want to make. I couldn't have made a film that would draw a bigger bullseye on my chest than that one. I knew my second time out that I was going to be walking into a buzzsaw, and I basically went right for it. Although the reaction elsewhere was pretty good, in the United States we got really hammered. A lot of them were punishing me for doing what I wanted to do. Reviews saying, 'After sex, lies, and videotape, Steven Soderbergh could have done anything he wanted. And, unfortunately, he has'. I think Kafka was taken more seriously than I wanted it to be. I thought it was supposed to be sort of fun. What was really strange was the proprietary attitude that a lot of American critics took to this specific icon. It was an attitude that would have been justified for Europeans to take, but they didn't - they were happy that it wasn't a biography, that it was sort of a fantasy of Kafka in which all his life, and his work, diaries and letters were mixed up together. They were relieved, but in America they were just pissed off." Still, he claims that he does not regret this particularly chastening experience. "Part of what I like about it is the hubris of it," he admits. "And there are isolated sequences that I think are some of the best things I've ever done, things in the film I'm very proud of: chiefly the performances. I got to work with Jeremy (Irons) - one of my favorite actors - Alec Guinness and Ian Holm. I wanted the opportunity to make an Expressionist film, and it was a film in which I felt completely connected to the protagonist." Soderbergh's third feature, the forthcoming King of the Hill, is a superb period piece based on A.E. Hotchner's memoirs of St. Louis in the 1930s. Centering on the attempts of 2-year-old Aaron to survive alone in the unforgiving Depression environment when his mother is confined to sanatorium and his father goes to sell watches door-to-door in neighbouring states leaving the boy with no money and the scant advice to "be a mensch", it again might not seem the natural next step for someone who is best known for his examination of adult sexual mores. For Soderbergh, however, there is a link between all three of his films to date. "They share protagonists who are somewhat confused, who are trying to make sense of the world around them, who are somewhat disconnected," insists Soderbergh. "So although they're externally extremely different, they all have thematic similarities. In many ways, King of the Hill is a strange prequel to sex, lies... It's exploring how somebody becomes disconnected and ends up like James Spader. It's about how a child is taught to be emotionally remote - and I think that's what drew me to the material." There is, of course, considerable irony to be found in this preoccupation with the alienated and the "disconnected", given the director's own self-imposed exile on the fringes of Hollywood. He reacts with horror at the suggestion that he might one day move from his Charlottesville, Virginia home to Los Angeles, and firmly maintains that he will continue with his uniquely personal approach to any future projects. "I'm unable to make a movie in which I can't connect with the protagonists... if that makes it less mainstream, then that's just the way it's gonna be," he admits. "I'll keep doing it until nobody wants me to make a movie any more. I'm happy with my career - sex, lies has allowed me to make two films that I really wanted to make, and I was allowed to make them as I saw fit. And that's a real luxury. On the other hand, every filmmaker wants their work to be seen. You don't really want to make the cinematic equivalent of an unpublished novel." As we speak, this remains a distinct possibility for King of the Hill, at least in the US. Clearly segregated as an arthouse movie, despite being Soderbergh's most accessible effort to date, it is currently playing at just 40 screens nationwide, and has all but exhausted its limited promotional budget. "I don't want a big audience," he sighs, "but I look at King of the Hill and I think there are enough people who might enjoy the movie, who I wish would go see it. But that's the one thing that I cannot control. As Sam Goldwyn said, 'If people don't want to see a movie, there's nothing you can do to stop them'." Soderbergh now has another two years' work already slated, including plans to take on John Kennedy Toole's cominc novel A Confederacy of Dunces and, before that, a remake of 1948's Criss Cross, in which, with typically uncommercial instincts, he plans to expand on the original's use of different timeframes running concurrently. ("I'm very interested in non-linear storytelling," he says, disingenuously.) It may even be a big-budget star vehicle, the one thing likely to turn his uncompromising quirkiness into serious career trouble. "The reason I haven't yet turned into a cult failure is because I've yet to make a film that people have expected to make a lot of money." says Soderbergh. "So, until I make a $40 million movie with stars in it - which is conceivable - that is expected to make money and then doesn't, people's perception of me is not going to be anything other than an interesting, responsible young filmmaker..."

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||