|

|

||||||

|

|

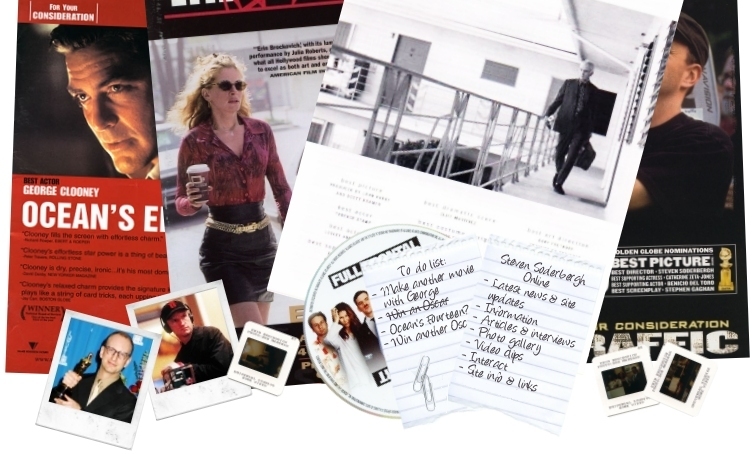

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

Go! Go! Go! “The great danger for any

artist is to find himself comfortable. It’s his duty to find the point of

maximum discomfort, to search it out.” To the outside world, it seems that in Hollywood you either make it or you don’t. But it’s a little more complicated than that. You can languish as much in development as out (but drive a better class of car). You can make bad movies and no one will care. You can make good movies and still no one will care. You can date beautiful women who would never have given you a second look if you’d bussed their tables. You can become nearly as celebrated for living down your promise as for living up to it; you can even make a career out of it. Ever since his second feature, sex, lies and videotape, won him the Palme d’Or in 1989, beating out cinematic titans such as Shoei Imamura and a pipsqueak named Spike Lee, Soderbergh has been living down the boy-wonder label he got stuck with. Who could blame him? He was only 26. He has made eight features since. Some were misfires, none made much money, and all of them were gutsy, in part because each new film seemed a departure, in form and content, from the last. It was with Out of Sight, though, that his industry profile once again began to rise. In the last few years, it has continued to climb nearly as fast as Soderbergh can make movies, which, given that next month he begins shooting his fifth film in four years, is pretty damn fast. Critics have greeted the recent work with enthusiasm, and this year’s Erin Brockovich, a divertissement with a social conscience, has also done exceptionally well with audiences - with over $100 million in domestic returns, it’s an unqualified box-office success. The film is a solid achievement for Soderbergh, a director who had yet to prove he could turn a large profit on mainstream material. What made that achievement more impressive was that when Erin Brockovich opened in March, only seven months and one week had passed since the release of Soderbergh’s last feature, an exercise in fractured storytelling called The Limey. It’s December now, and if Erin Brockovich is looking better than ever, with its star, Julia Roberts, in line for an Academy Award nomination, it’s because this week yet another Soderbergh movie, Traffic, opens in theaters across the country. An assured gloss on the drug war as lived and endured by half a dozen central players in Mexico and the United States, the new film is radical on a number of counts, including the fact that it’s almost unheard of for an American director to release two features in a single calendar year. You’d have to sift through the B-movie ranks or return to the glory years of the studio system, when the likes of Hawks and Hathaway would make two, sometimes three pictures a year, to find directors who worked this fast, albeit with all the advantages of factory production. Or you could just turn back to 1997, when Soderbergh released his low-budget conceptual parlor trick Schizopolis and the documentary Gray’s Anatomy, featuring monologist Spalding Gray, within a single month of each other. Soderbergh is fast, very fast, but that’s not what makes him the most

exciting young director in the country. A cinematic polymath who has also

written, acted in, edited, photographed and even done sound on some of his

own films, Soderbergh has in the past decade emerged as the American

director who has best absorbed the lessons of Hollywood and of independent

film alike. His films are smart, great to look at and listen to, and

filled with career-defining performances from the most obscure actor to

the most famous. At their finest, they are entertainments in the most

honest sense of the word - they please us as much with their immaculate

craft as with the depth of their feeling, moving us as adults, bewitching

us like children. Even at their most dubious (Schizopolis is as

irritating as it is liberating), his films are not guilty of the great

unpardonable sin of both contemporary Hollywood and the independents: They

never sell short their characters, their audiences or, just as important,

their maker. That’s such a rude question. Well, I’m trying to think. I just know that the world can be a pretty harsh place, and most people don’t get to spend their day doing something that they love, and so it’s really a pleasure to do that every day. I guess I don’t look much beyond that. And being an atheist…

You have a daughter, so I’d imagine that helps a lot.

You’d be pretty good as an ant. Soderbergh talked to Lester over a number of months in 1996, a particularly rough patch in the younger man’s life. Two years earlier, he had suffered a crisis of confidence while making his neo-noir The Underneath that left him unsure of himself as a filmmaker. That same year, he was divorced from actress Betsy Brantley. Soderbergh consequently spent a lot of time on airplanes and in hotel rooms. He worked on an unrealized project with filmmaker Henry Selick called Toots and the Upside Down House. He worked on the scripts for the horror films Mimic and Nightwatch and battled producer Scott Rudin over A Confederacy of Dunces (Soderbergh owns the rights now). He directed a play and watched a lot of movies. And he finished two films made on the fly and on the cheap, Gray’s Anatomy and Schizopolis, a lysergic indulgence that, among other things, lampoons Scientology. Working without the usual encumbrances - Schizopolis had a five-person crew - seemed to liberate Soderbergh, inspiring a sense of play and a sense of freedom, which is what had attracted him to Lester. But he still had his doubts. “What’s bugging me, I think,” he wrote on July 31, 1996, “is the possibility that this road that I’ve been encouraging myself (and everyone around me) to follow the last year and a half leads nowhere, or perhaps somewhere worse than the place I left. But what’s the alternative? Go back and make stupid Hollywood movies? Or fake highbrow movies with people who would be as cynical about hiring me to make a ‘smart’ movie as others are when they hire the latest hot action director to make some blastfest? I just don’t know where to turn.” Despite these spasms of soul searching, the book reads lighter than dark; it’s sarcastic and satiric by turns, almost as if to assure readers, and maybe himself, that he hasn’t become too self-involved. “Like many white liberals,” he wrote the same month that he anguished about Hollywood, “I have something of a Noam Chomsky fixation. I get all fired up after reading him and want to go out and protest shit… Then, within minutes, reality sets in and I start thinking about work and women and stuff.” That flip from the serious to the silly is characteristically Soderbergh, in person as well as in his work. It’s a small point, perhaps, but it’s telling that in both Out of Sight and The Limey, the beautiful leading men - George Clooney in the first, Terence Stamp in the second - both wear white socks with their ill-fitting dark suits during pivotal scenes. Even as the two stride purposefully forward - to rob a bank in one movie, to kill a man in the other - you can catch a glimpse of their imperfect humanity peeking out above their clodhopper shoes. This sense of human vulnerability and, at times, desperate failing, along

with the self-consciously jagged expressionism of his style - the

deconstructed scenes and time lines, the light flares and rough zooms -

bring to mind the restless individualism and storytelling that define some

of the better American movies of the late 1960s and early ’70s, from

The Graduate to Five Easy Pieces. But there’s a lightness of

touch to Soderbergh’s work that makes the films often more pleasurable and

less self-indulgent than these earlier touchstones. Soderbergh’s films are filled with men who are emphatically not the heroes of their own stories, from James Spader’s impotent roué in sex, lies and videotape to Benicio Del Toro’s compromised Tijuana cop in Traffic. Some of these antiheroes are fathers, like the regretfully imperfect family man of King of the Hill, based on A.E. Hotchner’s memoirs about growing up lonely in the Depression. In The Limey, Stamp’s gangster tough is finally done in, at least emotionally, by his failure to save his daughter, while in Traffic, Michael Douglas, as the nation’s new drug czar, plays a bureaucrat who doesn’t recognize the junkie in his own family. Women usually look better in Soderbergh’s work, often literally (he has a fondness for the good-looking ones). The most self-actualized of all of his characters is Erin Brockovich, but she makes an unlikely hero, and her final victory feels less like the triumph of the human spirit, as they love to say at the studios, than a matter of hard work and happenstance. Her push-up bras and clacking heels remind us that no matter how it turns out, there’s a part of Erin that will always struggle. “The stuff in the book didn’t seem that personal to me,” Soderbergh says now. “It was as revealing as I was comfortable being. The whole point was to demystify the process a little bit. There is a tendency, I think, for people who are interested in movies, either as a career or as a form of entertainment, to have this idea of what somebody’s life must be like who works in the film business. I was just trying to show some of the gristle. It’s a job, basically, and as with any job you go through ups and downs, and sometimes you have interactions with co-workers that don’t go well. For the 11 or so people who bought the book, I just wanted to remind them that, at least in my case, it’s not all parties and shit.” It’s just weeks before Traffic opens, and Soderbergh is busy promoting the film, conducting interviews and enduring photo shoots, even as he preps his next one, Ocean’s Eleven, an update of the wheezing 1960 Las Vegas heist movie with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and the rest of the Rat Packers. The new Ocean’s will star Clooney, an actor smart enough to stick with the director who proved he could hold the big screen, along with Don Cheadle and Brad Pitt. Production starts next month, but Soderbergh hasn’t yet figured out how he wants to make the movie. “I’m terrified,” he says, “terrified.” It’s hard to know if he’s joking. In preparation for Ocean’s, a film he somewhat mysteriously, and repeatedly, refers to as “a wind-up toy,” he made a study of the work of one of his friends, filmmaker David Fincher (Seven, The Game, Fight Club). “I’d been doing my little research,” he says. “I started talking to him about how I’d broken down a couple sequences. I said, ‘I’ve done some really good work on your cutting patterns. I think I’ve figured out a couple of things’. He was staring at me like ‘What the hell?’ and I realized that it’s all instinct for him. I was breaking it down, but he’s going on gut. I was talking to him about negative space being replaced by positive space, blah, blah, blah, and he just thought I was a psycho.” He’s clearly amused; it’s just one in a series of stories he likes to tell in which he ends up less than triumphant. Sitting for an interview in his cramped office on the Universal lot, surrounded by posters for films he didn’t make (Point Blank, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Les Carabiniers), Soderbergh can be surprisingly open on personal subjects, but his candor can feel curiously detached as well. When he talks about himself, at times it’s with the cool of a scientist observing a specimen. “I think I’m a pretty good parent,” he says at one point. “I was just a terrible husband. It’s less a women issue than it is a life issue. I live a large part of my life inside my head, and it just makes it really hard to make room for other people. It’s really that simple.” Soderbergh grew up in a house full of people, the fifth of six children. His father, a former marine, was dean of the college of education at Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge. He moved his family around a lot; by the time they got to Lousiana, Steven had lived in Virginia, Georgia and Texas, where he was born. His mother was a parapsychologist who did readings at the family home. “You know who my mom is?” he says. “She’s Beatrice Straight in Poltergeist, that’s my mom.” When Soderbergh talks about his late father, who died two years ago, and his child, even his palpable love for them feels as if it’s been put through the analytic wringer. Of his 9-year-old daughter, Sarah, who lives with her mother on the East Coast, he says, “That I see her sporadically is mitigated by the fact that it’s always been that way and it’s what she knows and it’s what I know and nobody’s complaining. We have, I think, a good relationship. Things seem to be calm, and as anybody who has a kid will tell you, it’s a relief to just have such undiluted, unconfused feelings about another human being. At least I know I can feel that for somebody. It took me a long time to reconcile that I am not - I don’t have the capabilities to be - a full-time parent. I’m just way too… I don’t know what, self-involved, workaholic, whatever.” This is, in fact, a man who cast himself, his former wife and his daughter as husband, wife and child in Schizopolis. When Soderbergh merrily sings out “Generic greeting” to his smiling wife/ex-wife, it’s hard to know whether to laugh or wince, especially since he is playing a role with which he admits he is not comfortable in real life. “The sort of traditional design of dad coming home every night and child

and wife and everything is something that completely freaks me out,” he

says. “You know, I went through a long time feeling really bad about that.

I think that as Sarah gets older it will change. Her mother is the

caregiver - not even the primary caregiver, she is the caregiver, and I

think it will not be until Sarah is much older that things that I can do

will sort of come to the fore. I think that as she becomes a teenager and

a young adult and an adult, I’ll be able to bring things to the table that

I haven’t been able to bring for her childhood. I hope so. But we’ll see.”

After Ocean’s Eleven, Soderbergh says, he’s leaving Hollywood

again, to live near his daughter. Personal filmmaking wasn’t new, but it had certainly lain dormant during the ’80s, a decade of overinflated, aggressively anonymous Hollywood productions. In 1984 and 1985, though, a handful of independently financed films, including Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise and the Coen brothers’ Blood Simple, signaled an industry shift to come. Even so, when sex, lies premiered in January 1989, the words independent film didn’t mean what they mean now. Before sex, lies, the movies that snared top honors at the U.S. Film Festival were titles such as Victor Nunez’s Gal Young Un and Bette Gordon’s Variety, movies that didn’t always get distributed, or, if they did, were distributed with minimal fanfare and money. In his book Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes: A Guided Tour Across a Decade of American Independent Cinema, indie rep and guru John Pierson argues that after Soderbergh’s feature, “It became the rule for the door to swing wide open for anyone who made the smallest splash in places like Sundance.” If it’s an overexaggeration to say that sex, lies and videotapes, Soderbergh and Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein made Sundance - and, by extension, changed the landscape of independent film - neither is it entirely false. Soderbergh’s film was followed by features from Reggie Hudlin, John McNaughton, Hal Hartley, Whit Stillman, Jennie Livingston, Bill Duke, Christopher Münch, Michael Tolkin, Todd Haynes, Richard Linklater, Julie Dash, Carl Franklin, Allison Anders, Nick Gomez, Tom Kalin, Tom DiCillio, Gregg Araki and Quentin Tarantino. That was the good news, and it happened in just three years. The bad news is that a number of these directors, even the best ones, often struggled with their next projects or simply disappeared, either into the ether or into Hollywood. Soderbergh struggled, too. At Cannes, when jury foreman Wim Wenders said sex, lies and videotape gave “us confidence in the future of cinema,” Soderbergh joked, “Well, I guess it’s all downhill from here.” For a while it was. Kafka, his interpretation of a script by Lem Dobbs, sank like a stone. The critics were brutal and audiences uninterested, and not without reason. Ambitiously mounted in Prague, the film was undone by its uneasy tone, which lurched from broad to oblique comedy, and leaden performances from Jeremy Irons, as the writer, and Theresa Russell, as a swaggering anarchist. To date, it is the only badly cast feature in the director’s body of work. Soderbergh recovered, at least critically, with King of the Hill, but this one too died at the box office. The Underneath, Gray’s Anatomy and Schizopolis followed, all box-office underachievers that found sympathy among reviewers, and then the call from Universal asking if he was interested in a script called Out of Sight, for which Cameron Crowe and Mike Newell, both bigger names at the time, were also being solicited. Soderbergh initially turned the script down, but changed his mind. The film is one of his best, and one of the finest American features of the ’90s - a genre movie that embraces and transcends its pulp pedigree to become at once a screwball romance and soulful caper film. Now comes Traffic, which, along with Cheadle, Del Toro, Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones, features smaller turns by the likes of Miguel Ferrer, Benjamin Bratt and Luis Guzman. Written by 35-year-old Stephen Gaghan, a loquacious Kentuckian who started at the Paris Review only to end up in Hollywood pitching story ideas for Baywatch Nights, the film survived a rocky development process that found it being sent into turnaround by Fox’s then-chairman and CEO, Bill Mechanic. Mechanic admires the film but says that he and Soderbergh differed on the original $25 million budget. “The script was great,” says Mechanic. “They were having trouble making the budget. We got to a point where we wanted some changes in the script, and Steve said that was the movie he wanted to make.” Although there’s more to the back-story, including Mechanic’s later departure from the studio, what’s most interesting is that the film got made. Traffic ended up at USA Films, a division of USA Network, cost $46 million (Soderbergh came in under budget because he forgot to use a couple million in contingency money) and, to hear screenwriter Gaghan, was made more in the spirit of independence than in the spirit of Hollywood. “It felt like the way filmmaking should be and rarely is when the budget gets up,” says Gaghan. “I mean, $46 million is not expensive for 110 speaking parts in 7 different cities. This movie would have cost $150 million for anyone who wasn’t putting the camera on his shoulder and sleeping in cheap hotels. It was just cool. I think that if this had been my first experience in Hollywood I would have been doomed, I would not have been able to do any of the other things that I’ve done. Truthfully, I want to make my own movie, and Steven has been great about that. I’d stayed away from the whole production rewrite thing, and took a job doing Blackhawk Down with Ridley Scott, because I’m a huge fan. I wrote a scene that I thought was one of the best things I’ve ever written, and the producer had a problem with it. I was talking about this, and Steven took my arm and said, ‘This is why you have to do this for yourself. You cannot give that stuff away. Don’t give it away’.” “I got to make the film I wanted to make,” Soderbergh said after sex, lies and videotape. “I got it out of my system.” To retrace his adventures in Hollywood, it’s clear that he still makes the movies he wants to. He directs big stars at bigger studios, but not because the stars and the studios are big - rather, despite the fact that they are. If nothing else, Soderbergh seems intent on proving that even with millions and tabloid-huge stars (Michael Douglas! Catherine Zeta-Jones - pregnant!), you can make a personal film. You can shoot your own footage - as Soderbergh did on Traffic, under a pseudonym - make the film grain swirl like dust and tint entire scenes a chilly midnight blue. You can use subtitles, rather than accented English, for long stretches at a time and weave together over 100 speaking parts with the skill of an underage Persian. You can turn cult favorite Benicio Del Toro into the soul of your film and miraculous team player Don Cheadle into its heart. Not incidentally, you can also make a Hollywood movie that says, without apology, that the domestic war on drugs has been a cataclysmic failure. You can, in other words, remain independent.

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||