|

|

||||||

|

|

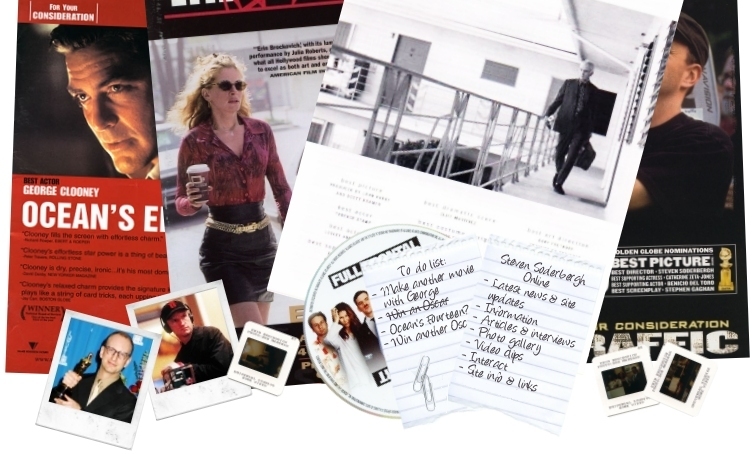

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

Steven Soderbergh: Practicing Surprise, Finding Success Eleven years ago, Steven Soderbergh's first film, Sex, Lies and Videotape, won the Palme d'Or at Cannes, making him, at 26, the youngest director ever to win that festival's most coveted prize. The title quickly entered the tabloid-headline vernacular (it would gain new relevance during the long melodrama of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal), but the movie itself was, and remains, refreshingly unsensational. Its spare, mordant comedy of sexual betrayal and romantic confusion seemed to touch obliquely on a widespread sense of unease, though Mr. Soderbergh's script refrained from specifying the causes of this mood (AIDS? economic anxiety? generational exhaustion?) beyond the troubled relationships of its four main characters. The film's extraordinary success was perhaps disproportionate to its merits, but sometimes it's necessary to make a big deal out of a small movie, if only as a gesture of revolt against the grandiosity of Hollywood. Sex, Lies and Videotape was a modest, well-made picture coming at the end of a decade dominated by loud, outsize blockbusters. Mr. Soderbergh, with the brave tactlessness of youth, was quoted in the press referring to two of the leading purveyors of such pictures, Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, as "slime, barely passing for human." He quickly became, like Spike Lee before him, a symbol and spokesman for the possibility that Hollywood's business as usual was not the only game in town - that serious, intelligent movies could once again flourish on American soil. As Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote in a report from Cannes, Mr. Soderbergh's anointment as the latest golden boy of the emerging American independent cinema burdened him at the outset with high expectations and set him up for a backlash of deflationary second-guessing. "It's all downhill from here," he remarked dryly in his moment of early glory, as the offers poured in. Happily, such pessimism, however facetious, has proved unwarranted. While the indie boom of the early 90's produced its share of hustlers, opportunists and flashes in the pan, Mr. Soderbergh's career has been as twisty as one of his movies. The seven features he made in the 1990's are astonishingly diverse in genre and style, ranging from the literary atmospherics of Kafka (his inevitable sophomore disappointment, ridiculed, unfairly, by some of the same critics who had championed Sex, Lies and Videotape) to the tenderness of King of the Hill, to the cerebral noir of The Underneath and to the low-key machismo of Out of Sight, his 1998 adaptation of an Elmore Leonard novel. While critics adored some of these movies, especially Out of Sight and King of the Hill, large-scale commercial success eluded Mr. Soderbergh. But even as he courted a mass audience, and Out of Sight helped to turn George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez into movie stars, Mr. Soderbergh continued to make formally daring, intellectually challenging films like Schizopolis in 1996 and The Limey last year. As many of his contemporaries - most notably Quentin Tarantino - have spawned legions of imitators and flirted with mannered self-imitation, Mr. Soderbergh has remained stubbornly idiosyncratic and has resisted the temptation to repeat himself. In the past year, he has shaken off the curse of precocious triumph and emerged from the limbo of being a hitless critics' darling, ascending at last to his rightful, if unexpected, place as a top Hollywood director. Erin Brockovich, which starred Julia Roberts as a crusading paralegal, was the first movie of 2000 to make $100 million at the box office. One of the few films so far this year to be embraced by both audiences and reviewers (with a few dissenters, including this writer), Erin Brockovich is likely to pick up a handful of Oscar nominations. If it does, Mr. Soderbergh may be in the enviable position of competing with himself: his new movie, Traffic, opens on Wednesday. It's certainly his largest, most ambitious movie so far, and it may also be his most accomplished. The two pictures could hardly be more different. Erin Brockovich is essentially a vehicle for Ms. Roberts's acting talent and movie-star charisma, which fight each other to a draw. The movie's story is as linear and conventional as they come: rags to riches, triumph of the underdog, working class ugly duckling into high-powered legal swan. Traffic, in contrast, is an ensemble piece, a dense weave of stories grounded not in a character but in a charged, topical theme - the drug war, seen from all sides of the battlefield. But different as they are, and as much of a departure from his earlier work as each one seems to be, both pictures are stamped with Mr. Soderbergh's unmistakable, if sometimes elusive, style. Over the years, Mr. Soderbergh has developed a striking visual and narrative approach and has honed his instinctive feel, already impressively evident in Sex, Lies and Videotape, for the expressive capacities of the medium. At his best - in King of the Hill, Out of Sight, The Limey and Traffic - he marries thrilling technical precision with an unobtrusive respect for acting. While he has clearly been influenced by earlier filmmakers like John Cassavetes, Jean-Luc Godard and Orson Welles, he has avoided the traps of homage and pastiche, the glib quotations and presumptuous mimickings so irresistible to his contemporaries. Mr. Soderbergh, with his studious attention to film language, his formalism and his thoughtful application of craft, is more modernist than postmodernist. Rather than trafficking in shock, his movies aim for the rarer, more valuable effect of surprise. One astonishment of Sex, Lies and Videotape was its unassuming air of self-confidence. As he has matured, Mr. Soderbergh has demonstrated a remarkable ability to trust not only his own instincts but the abilities of his actors and the intelligence of the audience. He assumes, as few American filmmakers dare these days, that you will pay attention, and your attention is rewarded, at the minimal, pleasurable cost of momentary confusion. The opening of Erin Brockovich is a tour de force of disorientation, as Ms. Roberts's character endures a humiliating job interview, a car accident and the desperate anxiety of impoverished single motherhood. The scenes play with our sense of time and subvert the lazy sense of narrative rhythm inculcated by bad movies and commercial television. Mr. Soderbergh allows some scenes to play on for an extra beat or two, as though to capture the awkward pauses of everyday experiences, and cuts others short to create a feeling of dread and implication. The car accident, which other directors might foreshadow with hackneyed cross-cutting or portentous music, takes place at the far edge of the screen, just at the moment our minds have wandered in anticipation of the next scene. In the long

run, the film's small surprises can't quite compensate for its overall

predictability, but Erin Brockovich at least proved that Mr.

Soderbergh's vision could assert itself within conventional parameters. It

could just as well be argued, though, that he had already proved as much

at least three times: in King of the Hill, a coming-of-age story

set during the Great Depression; in Out of Sight, a romantic crime

caper; and with the spare, almost classical revenge plot of The Limey. The story in Traffic is almost dizzyingly complex, with three main narrative lines, a dozen major characters, too many strong performances to list and nearly 100 different locations. The action takes place in Tijuana, San Diego, Cincinnati and Washington, and Mr. Soderbergh, who was the cinematographer (credited under a pseudonym) as well as the director, has used a variety of filters and film stocks to give each place its own look and texture. The cast includes Soderbergh stalwarts like Don Cheadle and Luis Guzman, as well as Michael Douglas, Amy Irving and, most astoundingly, Benicio Del Toro in two languages, Spanish and English. A director who began his career with a deft chamber piece has now at last attempted a symphony. Is it a populist art film or an especially arty popular movie? Is Mr. Soderbergh an independent who has infiltrated Hollywood, or was he always a mainstream director in maverick's clothing? Such questions are based on rather wobbly distinctions, the kind Mr. Soderbergh, early on, seemed likely to uphold. Now, at the top of his game, he may help to abolish them, which would be good news indeed.

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||