|

|

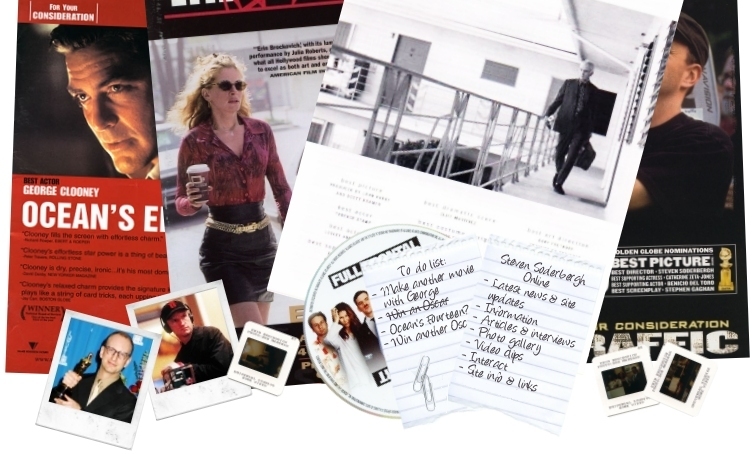

CALENDAR

8th February: Side Effects released (US)

15th March: Side Effects released (UK)

THE FANLISTING

There are 445 fans listed in the Steven Soderbergh fanlisting. If you're a Soderbergh fan, add your name to the list!

UPCOMING PROJECTS

LET THEM ALL TALK

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

KILL SWITCH

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

Now available from Amazon.com:

Haywire Haywire

Contagion Contagion

Now available from Amazon.co.uk:

Contagion Contagion

DVDs that include an audio commentary track from Steven:

Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection

Point Blank Point Blank

The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition) The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition)

The Third Man - Criterion Collection The Third Man - Criterion Collection

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

ADVERTS

|

|

|

|

The Traffic Report With Steven Soderbergh

By Darrell Hope

(DGA Magazine (Vol. 25 - 5), January, 2001) For some cultures, 13 is the

age at which a boy becomes a man. For Steven Soderbergh, 13 was the age at

which he became a filmmaker. The Baton Rouge, Louisiana, native came to

Los Angeles shortly after graduating high school and worked as a freelance

editor before returning home to polish his craft as a director by shooting

documentaries and shorts. Soderbergh's feature debut, sex, lies, & videotape, captured the

prestigious Palme d'Or at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival and catapulted him

to the forefront of American independent film. Since then he has completed

ten feature films including the indie films King of the Hill,

Schizopolis and The Limey, and more mainstream fare like Out

of Sight and Erin Brockovich.

Soderbergh's latest film, Traffic, is the ambitious weaving of

three stories that show the outside, inside and underneath of the drug

trade and is sure to instigate dialogues and debate. The film features a

huge cast that includes Steven Bauer, Don Cheadle, Benicio Del Toro,

Michael Douglas, Albert Finney, Amy Irving, Dennis Quaid and Catherine

Zeta-Jones and settings in Washington, D.C., Ohio, San Diego and Mexico.

The complexity of the film is almost a

metaphor for the director himself, for as he's putting the finishing

touches on Traffic, Soderbergh's also prepping his next feature,

a remake of the Rat Pack classic, Ocean's Eleven, with his Out

of Sight star George Clooney. And he still finds time to devote to

the DGA's Independent Directors Committee which he helped found.

Soderbergh, who recently took top honors at both the New York Film

Critics Circle Awards and the National Board of Review for both Erin

Brockovich and Traffic, revealed to DGA Magazine how he keeps

track of all of this Traffic.

What made you want to do a film about the drug wars?

It was something that I'd been interested in for a while. I didn't want

to make a movie about addicts but I didn't know what form it should

take. Then Laura Bickford, one of our producers, said, "I got the rights

to this miniseries that ran in the U.K. called Traffik." I

remembered it and said, "I think that's a movie; can I jump on?" We

started looking around for a writer and read this script by Steve Gaghan

about upper-class white kids at Palisades High involved with drugs and

gangs. He seemed perfect, but he was writing a drug movie for Ed Zwick.

Gaghan said, "Let's ask Ed if he'll combine the two projects." To his

credit, Ed said, "Let's do that. I'll come on board as a producer with

my partner and you can direct it." Then it was just a very lengthy

process of getting the script together. I remember having conceptual

discussions with Gaghan while I was shooting The Limey in October

of '98. We finished the outline before I went off to shoot Erin

Brockovich. When I got back he had a first draft, then we did just

numerous drafts after that. The draft we shot had 163 pages with 135

speaking parts and featured seven cities that we were shooting nine

cities to represent, all on a 54-day schedule. It was a real scramble.

How was it having two other directors,

Ed Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz, as producers?

It's actually great because they understand when to be close and when to

be far away because they've directed movies and have a very good sense

of when they're needed. So it was great for me. They were just a great

resource and totally supportive. On the couple of things that I've been

involved with as a producer I tried to be the same way, which is, "you

let me know what you need me to do because I want it to be your movie."

How about the studio?

USA totally left us alone. We came in $2 million under budget, which

helps. We moved quickly.

I imagine that's where your DGA team

came in very handy. Tell us about them.

My 1st AD, Greg Jacobs, has been with me since King of the Hill.

He's a key part of this and it's like having another filmmaker there for

me. Our second was Trey Bachelor, who we've also worked with before. And

we had a couple of new people who I liked a lot who I think we're going

to keep with us. With

all of the moves and all of the characters, it was very, very

labor-intensive for the AD crews. Shooting on the streets in Mexico,

control is an illusion. You need people who are well prepared enough to

be able to improvise, and also who know me. Greg's got backup plans on

top of backup plans because he knows I'm going to get there and say, "I

changed my mind. I want to shoot this direction," or "Pull that vendor

from over there, pay him $50 and get him in the shot." He's always ready

for that. Basti Van

Der Woude, our 2nd 2nd AD, who was new to our crew and has worked on a

lot of big budget studio Hollywood movies, said, "I cannot believe how

fast you guys move and how quickly you accommodate radical changes. I've

never seen anything like it." We try to be really light on our feet.

What made you decide to shoot this movie

yourself?

It was something that I had been working toward. I shot my short films

and Schizopolis myself. Then I started operating on The Limey

and on Erin and was really leaning in that direction. I knew

Traffic was going to be a real run-and-gun movie. It's all part of

just trying to get as close to the movie as I can. But I had

underestimated the luxury of being able to walk away from the set for

ten minutes and just clear my head. You can't leave the epicenter of

whatever you're shooting for an instant. It was relentless, but so

satisfying. How

did that affect the way you worked with the actors?

I think they really like the proximity. I stopped using video taps some

time ago because I felt it was creating a distance between the

performers and myself. I think they like my operating the camera because

two things happen. One is, subconsciously, it becomes harder to lie

because you know that you're being seen and if you show up with

something that's not true you're going to get busted. The other is, that

same proximity results in a trust and if we shoot something and I put

the camera down and give a note, it's a lot different than making the

march from video village to come give a note, or worse yet, giving it

over a megaphone or God knows what. It just makes them feel more

comfortable and when I go, "We got it," they know that we got it.

Michael Douglas said that he likes the

way that you work because you keep the cameras out of the acting space.

How do you figure out that boundary?

A lot of it's instinctual. I watched a lot of Ken Loach stuff because

his movies have that real vérité aesthetic and you believe it. I looked

at how he would frame, how far away he would be, what the length of the

lens was, how tight the eyelines would be, depending on where the

characters were. I noticed that there's a space that's inviolate, that

if you get within something, you cross the edge into a more theatrical

aesthetic as opposed to a documentary aesthetic. I was very conscious of

that when we would set up stuff and I would start looking as to how I

wanted to shoot it. I would tell the assistant cameramen all the time,

"This is not about perfection, I don't want to give people marks; I

don't want them thinking about that stuff." You don't want them

thinking. You want them being.

What kind of camera were you using for

the hand-helds?

We used the new Millennium XLs, which are extraordinary. They're even

smaller and lighter than the new high-def cameras that Panavision and

Sony created. With their lightweight zooms and a small mag, there wasn't

anyplace I couldn't get with that camera.

What other techniques did you use to

assist the story with the camera?

The issue of how to distinguish the three stories visually arose about

and I decided for the East Coast stuff, tungsten film with no filter on

it so that we get that really cold, monochrome blue feel. For San Diego,

diffusion filters, flashing the film, overexposure for a warmer blossomy

feel. And for Mexico, tobacco filters, 45-degree shutter angle whenever

possible to give it a strobelike sharp feel. Hopefully those

distinctions would be enough to bring you back into each story line

after you cut to somewhere else and come back. Then we took the entire

film through an Ektachrome step, which increases the contrast and the

grain enormously. I'm going through a phase where I'm in love with

degraded grainy contrasty imagery, stuff that I think you'd have

difficulty talking some cameraman into doing. When the film reaches its

release print stage, it will have gone through seven generations.

This must have been a bear to color

time.

It's really hard to predict what the Ektachrome will do to a given image

because what we're doing is we're going camera-negative, timed answer

print, then Ektachrome dupe of that answer print. Because that's a

positive Ektachrome, negative I.P., inter-negative release print, it's

really hard to look at a first generation, extrapolate the five steps

and go, "I think that's bright enough." There'll be stuff that you

think, "Oh, there's no way I'll see it in the shot." Then it comes back

and you take it through all the steps, you go, "Ah, it's not bad." I've

seen the film a lot in the Ektachrome stage and I like the way that

looks. Then I go back and I look at the answer print and it's completely

different and I have to remember, "OK, is that just what the Ektachrome

is doing or did we brighten that since the work print stage?" So the

Ektachrome is reflective of the work print but not the answer print. It

was really complicated.

After having done all this to the film

stock did you still edit it on AVID?

Yes. AVID is such a great tool. For a movie like this, where we did

a lot of restructuring in the editing room, it's a dream. We were

trying, I remember very late in the process we were starting to get the

movie down to a manageable length. The first cut was 3:10 and what you

saw was 2:20. There's 45 minutes of complete scenes that I liked that

just had to go. I kept watching the movie over and over in its entirety,

which, believe me, gets boring. But I found that if I reached a section

of the film that I didn't look forward to seeing again, it meant

something was wrong. Either the pacing was off or the scene itself was

not cut properly.

How long were you editing?

We wrapped at the end of June and we locked the first week in

October. I kept going back and tweaking stuff. I went back and reshot

things like the scene with Catherine visiting her husband in jail

because it wasn't emotional enough. A couple of the action-oriented

sequences were missing key pieces of coverage, what I would call

geography shots, so that you were clear exactly where you were at a

given moment like the scene where Frankie Flowers gets killed in the

parking lot. There are some key shots there of the guy in the window

that were new to the version you saw that I'd just shot the weekend

before. Now you understood the layout clearly and you understood why he

couldn't kill him until that moment. Before that, the scene was a little

iffy. I thought, I've got to watch this thing for 20 years so let's run

down to San Diego and get it over with.

Although Traffic is rated R, I

understand you were prepared to release it as an NC-17.

In the midst of all this discussion about the ratings there was some

concern on our part that the film might get an NC-17. We were resolved

to take the rating if we got it and not recut. But as it turned out, we

got an R. I was surprised.

Do you agree with the DGA's stance that

the MPAA rating system needs to be overhauled?

Yes. A group of us from the DGA's Independent Directors Committee

met with [MPAA President Jack] Valenti a month before this whole FCC

thing came down, because it affects independent filmmakers a lot more

than studio filmmakers. Independent movies tend to get rated more

harshly for reasons that we can't determine.

We said, "There needs to be a legitimate

adult rating that doesn't have a stigma attached to it. The filmmakers

want it; the public needs it." We discussed ways in which that could

take place. Then this whole thing broke in a big way publicly with that

FCC report. There's no question in my mind that the ratings system needs

to be updated. Things are different now. You've got to be sensitive to

the culture and the issues that are in the air for parents. Personally,

I was glad this whole thing blew up because it has nothing to do with

censorship; it has to do with responsibility. We need to take some

responsibility, so do the studios, so does the MPAA. Everybody has got

to get together and go, "This is the right thing to do for the

community, to have a rating system that is more accurate and

successfully keeps children from seeing films they should not see." I'm

glad it came to a head because now something is starting to happen.

You joined the Guild in 1993. Since that

time the presence of independent directors within the DGA has gotten a

lot stronger through programs like the Low Budget Agreements. Legend has

it that you were a factor in the creation of that program.

I doubt the cause and effect was that clear, but I called the DGA

before I went to make Schizopolis and Gray's Anatomy and

said, "I think I'm going to have to resign from the Guild because I'm

making these two movies for this amount of money and there is no way I

can make them under current Guild policy." The Guild said, "There is.

You send us two documents, one for each film, describing exactly what

you're doing, what the budget is, what the crew is, and who's doing

what. We will find a way to make this work."

We were able to come up with an agreement

that if I ever got paid anything for either of these films, that money

would be subject to pension and health, and I went and made the movies.

I'm sure I wasn't the only person who made that call to the Guild and

maybe enough of those calls came in to where somebody said, "You know

what, we've got to get on this because some of our younger Guild members

who are going to be the future of the Guild are calling us and saying I

want to work in a way the Guild can't accommodate." So hats off to the

DGA because more than any other organization, it has its ear to the

ground. As far as the

low-budget agreements go, if you call as soon as you start thinking

about a project, the Guild will bend over backward to make it happen.

Considering all the new technologies

that are coming, do you think the DGA is making adequate preparations

for the future? I'm very confident in the Guild's ability to ride all that stuff. I

think [DGA National Executive Director] Jay [Roth] and [DGA Associate

National Executive Director] Warren Adler and [DGA Assistant Executive

Director] Elizabeth Stanley are in the trenches of how do we deal with

these new issues. I think they're really on top of it. They're watching

very closely and listening very closely, which is half of it. I'm really

confident in the Guild's ability to move in whatever direction it needs

to move. Everybody's going to be playing catch-up. The point is that you

don't want to be caught napping when you should be catching up. The DGA

is pretty savvy about that stuff.

One of the things I noticed as a new

alternate to the Western Directors Council, is there's this overwhelming

sense of pragmatism. This is not a place to filibuster; it's a place to

get things done. It doesn't have to be pretty, it doesn't have to be

perfect, it has to work. I really like that energy.

Speaking of energy, are you shooting

Ocean's Eleven yourself?

Yes. I think it'd be hard to go back to insert someone into that

process having now taken someone out of it, or inserted myself into it.

What are you doing differently on

Ocean's Eleven?

I shot Traffic on the fly but I'm going to storyboard

Ocean's Eleven because although there aren't as many characters as

in Traffic, there are several physically complex scenes where a

lot of things are happening with a lot of different people at once and

you need to be very clear where you are at all times. That requires

sitting down and drawing out how you're going to do that so people don't

get confused and we can sell the thing and have it be exciting.

Considering what you learned on

Traffic, is there anything you would change about Erin Brockovich?

I don't think so. If anything, it makes me feel like the choices we

made from the script stage through shooting and finishing the film were

the right choices for that movie. The challenge in Erin was to

restrain myself in certain key areas and to never insert myself between

her and the audience. I'm used to waving my arms a little bit

directorially and it was a really good thing for me to back off. My grip

on that movie was every bit as firm as the movie that follows and the

movie that preceded it, but it was just a different grip, and half of it

was a grip on myself. There was a real pleasure in really servicing the

material and not getting in the way. I respected the real Erin so much

and wanted to have it turn out well, and it taught me for Traffic,

how to find a balance between being entertaining and dealing with a

serious underlying theme. It was a good warm-up.

Although you've done studio films,

you're still perceived as an independent director. In this era where the

studios often operate more like distributors rather than production

entities, what makes someone an independent director?

It's really hard to make those distinctions anymore. Especially

because there are some independent companies and distributors who are

more obsessed with the potential commerciality of a given film, albeit

on a smaller scale, than the studios are. The other day, I saw this

extraordinary new film by Christopher Nolan, Memento. I was

stunned. Every distributor in town had seen it and had not picked it up.

They only just signed a distribution deal with Newmarket Films. I

thought, "That a great movie like this has trouble getting picked up, if

that doesn't signal the death of the so-called independent wave, I don't

know what does." That's depressing. It's harder now for people coming up

than it was when I came up. It was more difficult to get a film made

when I started, but it was easier to get it distributed. Now there are

just so many movies that it's rare. People are not buying that many

finished movies anymore. The great thing about it is how Darwinian it is

and how no matter how bad it seems to get, some filmmaker somewhere

always does something extraordinary, finds a way and somehow the thing

emerges. Right now as we speak, somebody is finishing a movie that six

months from now we're going to be talking about. I find that incredibly

exciting. Anything

you have your eye on beyond Ocean's Eleven?

There are a couple of things that I'm working on, but it's usually

when I'm further along that I figure out what the antidote for the

current film is. After Traffic and Erin I wanted to do

something that had no social value whatsoever, which was Ocean's

Eleven. Maybe

you should do a Star Wars episode.

I'd love to do a Star Wars movie. But it would be like three

guys sitting around talking about what they did.

|

|