|

|

||||||

|

|

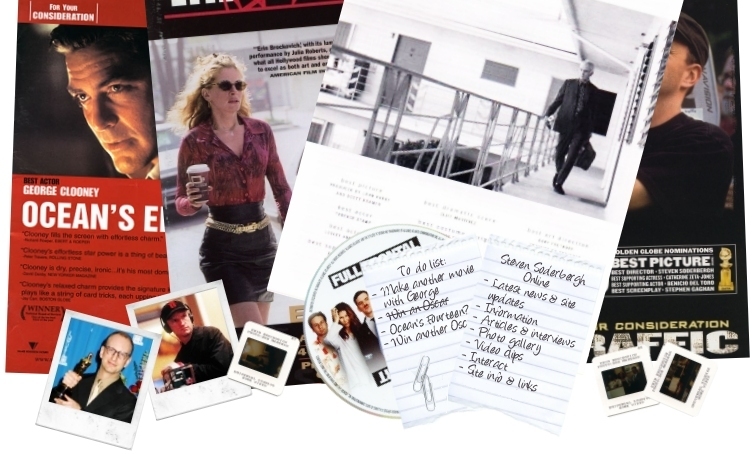

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

Protesting Another Misguided War Director Steven Soderbergh

taps into intense feeling with Traffic, his much-lauded exploration of the

nation's futile effort to fight drugs. "It was like they'd been waiting for someone to ask them about this

issue," Soderbergh says. "I've done a lot of these previews and it's never been that intense," he says. "They wanted to talk about this." Turned down by every major studio and finally produced by USA Films, Traffic barely got made at all, yet now looks to be connecting with a slowly building critical mass of thought questioning both the efficacy and wisdom of the long-accepted military approach to combating drug abuse that took shape almost 30 years ago during the Nixon administration. Even outgoing U.S. drug czar Gen. Barry McCaffrey, said in an interview at the end of the year (without reference to the film), "We've got to drop the metaphor of 'the war on drugs'." Indeed there are some signs the political winds are beginning to shift. In November, California voters passed Proposition 36, which will divert nonviolent drug users from state prison into treatment programs. New Mexico's Republican Gov. Gary E. Johnson is an outspoken foe of the drug-war approach to the problem. And in the film, California Democratic Sen. Barbara Boxer makes a cameo appearance at a Washington, D.C., cocktail party lobbying for the passage of a treatment-on-demand bill. (She's among several senators making cameos, including Utah Republican Orrin Hatch, who has taken flak for appearing in an R-rated, politically charged film.) "Personally," says Soderbergh, "I just felt like it was time to try to get a handle on this subject and that a movie was a really good way to do it." But drug movies - or for that matter, films with a political theme - generally have not done big box office. Rebuffed by studio executives who didn't see the commercial viability of his idea, the director lowered himself to the level of Hollywood shorthand. "I kept describing it as Nashville crossed with The French Connection, but I don't know that that was helping." Traffic opened in Los Angeles and New York on December 27 to some of the best reviews of the year. It went into wider national release on Friday, boosted by the buzz of critics' awards (Soderbergh was chosen as best director by several critics' groups for Traffic and Erin Brockovich) and talk of an Oscar nomination for best picture. Based on a 1989 British television miniseries and relocated by screenwriter Stephen Gaghan (Rules of Engagement) from Asia and Europe to the Americas, Traffic employs three separate but interlocking story lines to illustrate, in the director's words, "a sort of Upstairs, Downstairs glimpse of what's going on, from how policy gets made to how the stuff [cocaine and heroin] gets from Mexico to a street corner in Cincinnati." Michael Douglas plays an Ohio Supreme Court justice tapped to be the nation's next drug czar whose conventional assumptions about the morality of the "war" are shaken by his own teenage daughter's addiction and revelations about the inner workings of the Mexican drug cartels. On the other side of the border, Benicio Del Toro plays a Mexican border policeman trying to uphold the law without angering members of his government who have a stake in the drug trade. "In some ways, I'd been researching a movie about the war on drugs for 20 years," says Gaghan, a native of Louisville, Ky., who had been developing a script about drugs and gangs at Palisades High School for producer Ed Zwick when Soderbergh and producer Laura Bickford found him. With Zwick's consent and "to his everlasting credit," adds Soderbergh, Gaghan's project was merged with the adaptation of the British miniseries for Traffic. Gaghan was sent on an extensive research trip to Washington, D.C., and the U.S.-Mexico border. He found out, among other things, that "an honest cop on the border has a life expectancy of 30 days," "how much Tijuana has changed, with drug addiction, prostitution and petty crime going through the roof" and that "7% of all people for the last 5,000 years in all cultures have been addicted to something." Stunned by the illogic of our national drug policy and laws that have made it necessary to build more prisons to house nonviolent users while education and treatment programs go begging, Gaghan was at first inclined to write a satire, a Dr. Strangelove about the war on drugs. But Soderbergh wanted something else. "He told me, 'I want it big. I want to do an epicí," recalls Gaghan. While the movie hardly condones drug use and contains some harrowing scenes of cocaine and heroin addiction, it refuses to demonize the drug culture; instead it brings it close to home. "I wanted to show this family in John Hughes country," says Gaghan, referring to the bland suburban habitat associated with the movies of the writer-director of Ferris Bueller's Day Off. "Ferris Bueller country, that's where it starts." Soderbergh says that the example set by Douglas' character, who comes to view the problem differently after finding his daughter in its midst, is true to life. "With the research we did, when you talk to law enforcement officials and say, 'Your 16-year-old is caught with drugs, do you turn them in to the cops?' And all of them said, 'No'. And that's the point. When it's your family, it's a health-care issue; when it's someone else's family, it's a criminal issue. "That's the problem with our policy right now: It doesn't address the disconnect that everyone feels." Traffic dramatizes some of the same facts uncovered in the recent Frontline documentary on PBS that showed several U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration officials stating publicly that the war on drugs has been, in effect, a gigantic waste of taxpayer money. Recalling a 1984 raid in which 12 tons of cocaine bound for the U.S. were confiscated and had no discernible impact on the availability of the drug, one DEA official said on camera, "That's when we realized at DEA that you better start focusing on something besides law enforcement." In the film, Douglas' Ohio judge is a conspicuous creation because despite what McCaffrey and the DEA have said about the failure of interdiction, it is still taboo for most politicians to say the same even in a year when both presidential candidates spoke about youthful indiscretions involving drugs and alcohol. "That was one issue that didn't get talked about in the campaign," says Soderbergh. "By the time somebody reaches 22, conservative estimates are that 75% to 80% have tried something. 12 to 15% of those people end up having a problem with it. But what happens to the others, who apparently like George W. Bush and Al Gore tried it and maybe even went through a very intense period but got out the other end and moved on? How do we address those people for whom it is not life-threatening? The zero-tolerance attitude doesn't track." Soderbergh and Gaghan brought different experiences with drugs to the subject. "I've had friends who've had problems, who are in that 12% to 15%, and for most of them moderation was not the issue," the 37-year-old Soderbergh says. "It was literally an all-or-nothing thing. Those are the people who need help and once they've gotten help, stay on [a program] for the rest of their lives. "But I don't know the difference between people who have a couple of cocktails every night and people who smoke a joint. Those are very similar things to me - mood-altering substances. I feel fortunate that it's not something that's ever played a part in my life that I had to deal with. It seems that in my family, none of us are very addictive personalities. For instance, when we're shooting, I'll have a cigarette at lunch, and when we're not shooting, I don't. I have a pretty good sense of the difference between enjoying something and needing it. And whenever that starts to happen, I back off. But I'm lucky." For his part, Gaghan says, "I do have an addictive personality. I've experimented with everything and some of my closest friends have died." Louisville, he says, was an incubator for an array of legal intoxicants. "It's a town where smoking cigarettes is jingoistic," he says, referring to the local tobacco industry. "It's a city that's all about booze, tobacco and horse racing." He recalls at an early age being tuned into the semantics of addiction. "In Louisville, there are a lot of euphemisms. I remember when an aunt or an uncle would disappear for two weeks, we were told, they were 'taking the waters', which I later learned meant they were drying out somewhere. It was a hard-drinking environment. In Kentucky, you learn how to drink bourbon." The movie scenes of bright, angst-ridden upper-class kids getting high after school are based on things Gaghan saw and experienced as a student at Kentucky Country Day. (In the script, he moved the action 100 miles up the Ohio River to Cincinnati Country Day School, a reference the school is protesting.) He estimates that 80% of his high school class (1983) had tried marijuana and "got drunk or high once every two weeks." Gaghan says he had hoped Traffic would help scare straight his Louisville friend and fellow writer, Robert Bingham, but Bingham (author of the novel Lightning on the Sun) died of an alcohol and heroin overdose a month before the movie went into production. Gaghan faults the politics and bully pulpit policy of the former Reagan

secretary of education and George Bush drug czar, William Bennett, as a

factor in Bingham's demise. "The reason he's dead is that he couldn't talk

about his problem publicly," says Gaghan, "because of the stigma, and the

stigma comes straight from William Bennett," whom he believes lent a

religious fervor to the war on drugs. "When you have a heroin problem, you

die in private." "You talk to any cop," says Soderbergh, "they'll tell you, education and treatment pays off like gangbusters. The supply? We're never gonna stop that." Yet as the movie attracts critical praise and opens wider across the country, the U.S. is stepping up economic and military aid to Colombia, where the war on drugs continues apace despite this being a strategy renounced by DEA officials, as shown by Frontline. Possibly the political climate will change with a new administration. But based on his law-and-order record as governor of Texas, President-elect Bush seems unlikely to risk endorsing a policy that might be considered soft on crime. "I don't know," says Soderbergh. "I feel absolutely that it's in the air right now. I felt that when the movie was threatening to fall apart last year, when we were bouncing back and forth between studios, and actors were dropping out and coming on and there was a question whether the movie was going to happen. I felt anxious because I felt this is the time to do this." Traffic is not full of hope, exactly, except for that inspired by the lonely courage of Del Toro's wily and oddly romantic border cop, and the transformation of Douglas' conservative judge. There is a climactic moment that seems to carry the filmmakers' clearest message, when Douglas, reeling from his up-close education in the drug trade, says to a gathering of reporters, "If there's a war on drugs, then many of our family members are the enemy. And how can you wage war on your own family?" "He's absolutely right," says the director.

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||