|

|

||||||

|

|

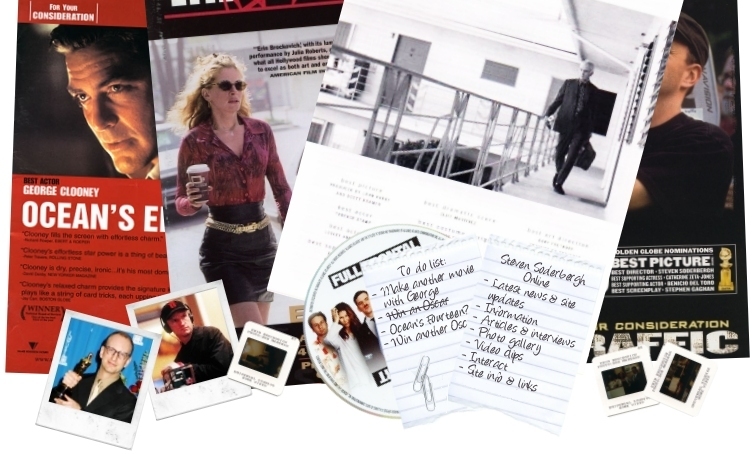

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

Steven Soderbergh Steven Soderbergh was 13 when he managed to talk his father into letting his sister drive him all the way across town to the theater where, in a sparse audience, he watched Alan J. Pakulaís All the Presidentís Men for the first time. ďThis is one of the great openings of all time," Steven Soderbergh said. He was leaning forward, elbows on knees, in the front row of a small upstairs theater on the Universal Studios lot. The bright image on the screen was entirely white, radiant and stubbornly monochromatic. The seconds crept by, bleached light spilling over the 38-year-old directorís expressionless, upturned face. "We should have timed it," he said. "I think it lasts 45 seconds." Suddenly: Wham! A gigantic typewriter key streaks into the frame and smacks onto the glowing white rectangle, now revealed as a blank sheet of paper. "Yeah," Mr. Soderbergh exclaimed quietly, like a football fan celebrating a solid tackle. Mr. Soderbergh was 13, a fresh arrival in Baton Rouge, La., where his father was a college professor and administrator. He had been grounded that autumn weekend in 1976 - he canít remember why - forbidden to attend a party that heíd been looking forward to, a newcomer hoping to make friends among the strangers. But somehow he managed to talk his father into letting his sister drive him all the way across town to the theater where, in a sparse audience, he watched Alan J. Pakulaís All the Presidentís Men for the first time. "I was really looking forward to the movie," Mr. Soderbergh said. "I was a huge Dustin Hoffman fan." It was a period in his life, he said, when he was really coming alive to film. He would go back and see his favorites again and again. He saw All the Presidentís Men about 10 times. "It is without question one of my favorite American films of all time," Mr. Soderbergh said. "And itís one that I looked to quite a lot while I was making my last two movies, Erin Brockovich and Traffic, because in both cases we were trying to make films about serious issues that were also very entertaining. "All the Presidentís Men is one of the better examples of a movie that managed to have a sociopolitical quotient and still be incredibly entertaining. Itís my sense that you can balance those things, and that the audience will sit still for it, even todayís audience, if they feel there is some real connection between the political content of the film and their lives." Mr. Soderbergh remembered spending the entire week before the opening of All the Presidentís Men in Baton Rouge reading the book by the Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, all about how that pair of unheralded metro reporters had doggedly transformed a peculiar late-night break-in at the Watergate office complex into one of the greatest newspaper subjects of all time, bringing down a presidential administration in the process. Handling Important Issues "I guess what impressed me most about All the Presidentís Men, and what still impresses me, is that there is really no reason why this movie should work," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Itís a story that everyone knew. I mean, the movie was released in 1976 and President Nixon had just resigned in 1974. And the movie climaxes with the protagonistsí making a huge mistake. And yet it works so completely. I never tire of watching it." But the movie has been even more prominent in his thoughts lately, as he made Traffic and Erin Brockovich. On Tuesday each received an Oscar nomination for best film, and Mr. Soderbergh received two nominations for best director. This is the first time that in one year the same director has had two films nominated for best picture and has also been nominated twice for directing them. "I took my cue from All the Presidentís Men in finding oblique ways to handle important issues while still making a film that is satisfying on a pure entertainment level," he said. "You donít want to destroy the pillars that these genres are built on. "I mean, Erin Brockovich is a pure David-and-Goliath story, a kind of Rocky film. Our hope was to make a good movie with that. And Traffic is more, to our way of thinking, in the vein of Z and Battle of Algiers and The French Connection, all very entertaining films with a sense of realism and of urgency." Influences Small and Large All the Presidentís Men settles in for its brief prologue, television images of a packed joint session of Congress awaiting the arrival of President Richard M. Nixon ("Look at all those old white guys," Mr. Soderbergh said), which blends into late-night shots of the Watergate complex and the dark figures of the burglars making their way into the national headquarters of the Democratic Party. The opening credits begin to roll. "I tried to duplicate this typeface for Traffic," Mr. Soderbergh said. He was referring to the narrow sans-serif type that Pakula used for the title credits in All the Presidentís Men. Mr. Soderbergh said he searched but could not duplicate the typeface exactly, so he settled on one that was close. "You notice, I did steal the placement," he said. The credits for both films appear not in the center of the frame, but in the bottom left-hand corner. "I just liked the feel of it, the simplicity," he said, and it was also, in the back of his mind, a kind of insiderís homage to Pakula. That director, who died at 70 in 1998, is also acclaimed for films like Sophieís Choice and Klute. The scenes of the break-in that open the film are dark and foreboding, but it is not immediately clear what creates a strange mixture of intensity and detachment. Nothing is really happening but dark figures moving through dark rooms. But then there is a particularly arresting image: The camera is outside, looking in through the window of a hotel across the street from the Watergate. The hotel curtains are half-drawn. A man is standing in the room, talking into a walkie-talkie. There is the sound of crackling and breathless exchanges of terse dialogue, but virtually no movement. "Wow, look at that," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Gordon Willis was one of the few cinematographers mixing color temperatures like this back then. Look at the greens and the oranges." It was so obvious, once Mr. Soderbergh pointed it out. The dark exterior of the hotel is a cold mixture of shadows and icy colors, frozen blues and arctic greens, while in the portion of the frame that shows the inside of the hotel room, from a light source apparently hidden behind the half-closed curtain, warmer amber hues take over, like a campfire on a tundra. And Mr. Soderbergh also noted how the director kept the camera utterly still. We remain hanging in the air, looking into the hotel room from outside, like a peeping Tom. We are so far away that we cannot read the expression on the actorís face and must, instead, focus on the crackling from the walkie-talkie. "A lot of filmmakers would have gone with the obvious thing here," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Weíd have a close-up here of the guy talking, or the camera would move inside the room. But it is so much creepier like this." It is an example, he said, of how a filmmaker in command of his craft - like Pakula - can inject emotion, in this case eerie tension, simply by playing against audience expectations. A small point, Mr. Soderbergh said, but telling. Later in the film he makes the same point about one of his favorite scenes, Mr. Hoffmanís nervous, late-night interview with an even more nervous Republican bookkeeper, played by Jane Alexander. "Look how they shot this," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Throughout the whole scene the camera remains the same distance away from both of them. It never goes in for a close-up. It never changes its distance at all." The camera ping-pongs between Mr. Hoffman (as Bernstein), sitting on a sofa, and Ms. Alexander, sitting on a chair opposite him. "By not going into a close-up and then releasing, by maintaining the same distance, it keeps the intensity building in the scene," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Normally, youíd go in and out. And shooting a scene that way can be effective, too. "But there is a different kind of energy that comes from maintaining the same shots. You just get a sense that these filmmakers are so secure, that they have complete confidence in their material and their performers." Only at the end of the scene does the camera pull back, to a shot of the actors facing each other across the small room. Ms. Alexander leans back in her chair and her head disappears behind a table lamp, as if she is hiding. It is a little signal that the scene is over, Mr. Soderbergh said, the setup for the transition. "This film is just so secure in its belief that you will be interested in the characters and the situations," he said. "There is no attempt to whistle up some dramatic high points. It is confident, but quietly so. Which is so rare now, you know. "I think youíd have a tough time making a movie with these attributes right now. I think if you went in and previewed this movie, you know, the way it is, 95 percent of the cards youíd get back from the audience would come back saying, ĎOh, itís too slow, itís too talkyí. Although the mitigating factor, I guess, is that the movie had in it two of the biggest movie stars of the time. So maybe if you did that today, you could get away with it. I donít know." Witnessing the End of an Era In Mr. Soderberghís mind, the fertile period in filmmaking that some call the American New Wave began in 1967 with films like Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate and ended in 1976, when All the Presidentís Men came out. Most people trace the demise of that burst of creativity to the releases of Steven Spielbergís Jaws in 1975 and of George Lucasís Star Wars in 1977, blockbusters that alerted studios to the lucrative potential of gigantic, audience-pleasing adventures. But Mr. Soderbergh said the era ended for him with the Academy Awards ceremonies for movies released in 1976. "Look at the five best picture nominees from that year," he said. "You had All the Presidentís Men, Bound for Glory, Network, Rocky and Taxi Driver. Now, I donít know about you, but one of those movies really stands out to me - Rocky - and itís the one that won. I happen to like that movie, but it does feel very different from the others to me." Those others, he said, were more typical of the fertile filmmaking era that was ending, while Rocky was the harbinger of the future, the feel-good epidemic that has infected American film for almost a quarter-century. "Those other four films all have a little more on their minds than Rocky does, and I guess thatís what I was responding to," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Because I was seeing a lot of movies at that time, a lot of foreign films, and I was drawn to stuff that had layers. Maybe I did also have a sense that that great era was coming to a close." Mr. Soderbergh raises up in his seat, like a prairie dog sniffing something in the wind, during the first scene in The Washington Postís newsroom, painstakingly reconstructed on a soundstage in Burbank. "There was a book that came out back then on the making of the movie, and I snapped it up," he said. "Mostly itís just a picture book, but there are some really interesting things in it. This newsroom was recreated down to the tiniest detail. They even flew in actual garbage from The Postís newsroom in D.C. for the garbage cans on the set." Perhaps that was a little excessive? Mr. Soderbergh smiled and shrugged. "I donít know," he said. "I think I can feel it." Toying with New Technology What grabbed his attention was the first use in the film of a dioptric lens with a split focus, a toy that was relatively new when the movie was made and that Pakula used to spectacular effect in the film. Essentially, the lens works like bifocal eyeglasses; there is an invisible line down the middle, sometimes vertical and sometimes horizontal, and the focal length is different on each side. The trick in using it, Mr. Soderbergh said, is figuring out how to hide the line in the shot so that the two focal lengths are not noticed and the image takes on a subliminally deeper and more three-dimensional feel. Sometimes Pakula uses one of the white, tubular pillars in the newsroom to disguise a vertical line, or the edge of a desk for a horizontal line. If used properly, one image can be very close to the camera on the left side of the lens while the image on the right is relatively far away, and both are in perfect focus. In All the Presidentís Men, Pakula uses the dioptric lens most frequently in the newsroom scenes. Sometimes he has Robert Redford (as Woodward) or Mr. Hoffman talking on the phone in extreme close-up on one side of the frame, while on the opposite side people are milling around in the newsroom in the background, and everything is in focus. There are also frequent scenes in which a television is playing on one side, showing moments from the Nixon White House years, while on the other side Woodward and Bernstein can be seen in contrast, working away on Nixonís downfall. "Itís used in such an interesting way in this movie, but Iím not sure what Pakula was up to with it," Mr. Soderbergh said. "There is no real obvious reason to use it. Maybe heís just trying to create this sense of being totally immersed in the newsroom. Otherwise, perhaps, if you are shooting Redford talking on the phone, he would be kind of isolated. This way, heís part of this larger group." The film does not rush itself, Mr. Soderbergh noted, but maintains a definite relentlessness. Information is parceled out - sometimes in humorous exchanges of dialogue from William Goldmanís script - one classic line after another, "Follow the money" being only the most famous, and sometimes in snippets of chatter during one of the half-dozen telephone scenes. "Itís so smart how they did this," Mr. Soderbergh said. "You get the scene where Redford is working on the phone, trying to get a small piece of information, and then you cut to the scene where you see what happens with that information once he gets it. Itís a great narrative device. Itís just good storytelling. It implies all the work that went into getting the information while keeping the story moving along." Itís all about the task of luring the audience from one scene to the next. Subtly Seducing the Viewer "Iíve begun to believe more and more that movies are all about transitions," Mr. Soderbergh said. "That the key to making good movies is to pay attention to the transition between scenes. And not just how you get from one scene to the next, but where you leave a scene and where you come into a new scene. Those are some of the most important decisions that you make. It can be the difference between a movie that works and a movie that doesnít." And the transitions in All the Presidentís Men, he said, are marvels. The movie does not race forward. There are no action scenes, no big dramatic moments. And the plot frequently dead-ends into unresolved cul-de-sacs. But the overall effect is thoroughly gripping. "The movie so much has the rhythms of real life in it," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Or are we just getting old? I was going to say you donít see movies that often today that just have the small moments in them where things are not accelerated, where people move at a real-life pace. But Iím wondering whether, for some people, their experience of the world isnít like that anymore, whether theyíre just sort of always overloaded and accelerated and thatís how they perceive the world. Maybe, to them, something like the slower scenes in this movie donít feel like real life." Stars at Their Ascendancy Jason Robards appears on the screen for the first time as The Postís top editor, Ben Bradlee, meeting with other editors behind the glass walls of his office. "Oh God, what a great performance," Mr. Soderbergh said. That, he said, was another astonishing element of the movie: how many of the biggest stars of the period and finest actors of all time came together and, in this one movie, did some of their finest work. "One of the things I thought about when I watched this while we were preparing Traffic was how itís such a varied cast in terms of the type of actors and what they can do," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Yet the fact is that they all still feel like theyíre in the same film. They occupy the same universe." Often, when different kinds of actors are thrown together - matinee idols with classically trained stage actors, stand-up comics next to Method actors - an artificial flavor takes over. Such a mix "would be absolutely crucial to making a movie like Traffic, especially since we were shooting in such a fragmented way with so many different locations," he said. "There is always one thing about a movie that Iím about to do that scares me, and that was what scared me about Traffic: how could I make sure all 115 actors felt like they were in the same film? And I came to All the Presidentís Men for help with that." Up on the screen Woodward and Bernstein hop in their car and head to the Library of Congress, searching for information. As they drive into the downtown Washington traffic, the slow march of the musical score by David Shire begins to play. "Thatís the first music cue in the movie, did you notice that?" Mr. Soderbergh said. "What is it, like, 35 or 40 minutes into the film? There is really very little music in this movie. The score is unbelievably good, but there is not much of it, like maybe 15 minutes in the whole film. Itís such an important lesson. I really try to be careful about that stuff, about not packing a movie with too much music." The Watergate reporting has stalled. Woodward and Bernstein are about to be sent back to the metro desk. So Woodward pulls his trump card, walking to a phone booth across from the old Executive Office Building ("We had a shot of that building in Traffic," Mr. Soderbergh said. "It looked more blue in our movie.") and calling his secret source, Deep Throat. Underground with Deep Throat A few scenes later they meet, lonely figures in a creepy, almost-vacant underground garage. The Deep Throat scenes are perhaps the most famous ones in the film. They come to dominate the story, yet there are really only three fairly short appearances by Deep Throat. "The scenes are just mind-boggling," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Everything about them. The way theyíre lit. The way theyíre shot. The dialogue. The sound. Look: this is Gordon Willis at his absolute best." Woodward wanders through the dark garage, his footfalls hitting like bricks on the otherwise hushed soundtrack. A droning air conditioner hums in the background. Finally, up against a pillar several yards away, he sees a dark figure (Hal Holbrook) illuminated by the orange flash of a cigarette being lighted. Cold and warm colors mixing again. "Itís just so perfect," Mr. Soderbergh said. At a cursory glance, the scene appears lost in gloom and colorlessness. But there are exceptionally subtle varieties of color and texture. "In his close-ups Holbrookís got a light right on his eyes, but itís maybe two stops down, at the very edge of perception," Mr. Soderbergh said. It does give the actor the look of an animal hiding in the forest at night, or a vampire. "And there is another light off to the side that just draws a line right around him, highlighting the side of his face. Look at him. Heís like a ghost." But when Mr. Redford appears to deliver his half of the lines, the look is quite different. Though still clothed in gloom, slightly warmer colors illuminate his face. "See, with Redford we get skin tones, but with Holbrook itís just completely monochromatic. Deep Throat is not even human." The Deep Throat sequences "are so beautifully constructed," Mr. Soderbergh said. "The power dynamic between the two of them is so very well drawn. No, I think they are really the heart of the movie." A Directorís Sleight of Hand Another scene draws Mr. Soderberghís admiration: the long sequence during which Mr. Redford, sitting at his desk, juggles two phone calls to learn why a $25,000 check from Republican campaign donors has turned up in the bank account of a Watergate burglar. Besides being a virtuoso piece of acting by Mr. Redford, the scene is intensely compelling and visually interesting, though it draws strength from the most subtle details, Mr. Soderbergh said. "Just watch," he said. "This is a single take. It must be, I donít know, six or seven minutes long." It is one of the newsroom scenes that uses the dual-focus lens. Mr. Redford talks on the phone, punching back and forth between the two calls, trying to control his growing excitement as he traps his quarry. At the same time, in the background, the newsroom is bustling. People huddle around a television, chat, make their own phone calls. "You have to watch very closely, but if you look at the edges of the frame you can see that the camera is very, very slowly zooming in on Redford," Mr. Soderbergh said. "Itís just so elegant and slow and gradual." And even though it is happening in an inconspicuous way, the tension builds. "Just amazing," Mr. Soderbergh said. Magic Ingredients When the film ended, Mr. Soderbergh stood and stretched. "Well, that was a treat," he said. He wandered back to the projection room, where he had to recover the two film canisters containing the movie. He carried one in each hand and wandered outside into the afternoon sunshine to wait for his driver. He considered how to explain why a movie like All the Presidentís Men works so perfectly. You can dissect individual scenes, but something larger is at work. Yes, the director, the cinematographer and the screenwriter were all working at their peaks. And yes, they made exquisite use of technical gizmos. And certainly the film was aided by the cast, in which every performer seemed to give one of the best performances of his or her career. But something else is going on, too. Something like luck. "This movie just has the perfect balance," Mr. Soderbergh said. "The perfect balance between all of the elements. Sometimes, if youíre lucky, you get that, and sometimes you just donít. You are always hoping for that alchemy to occur where everything in the movie is lifted up, because everything and everyone is working at the highest level. You hope for it, and you work for it, and sometimes you get it. And this is just one of those movies."

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||