|

|

CALENDAR

8th February: Side Effects released (US)

15th March: Side Effects released (UK)

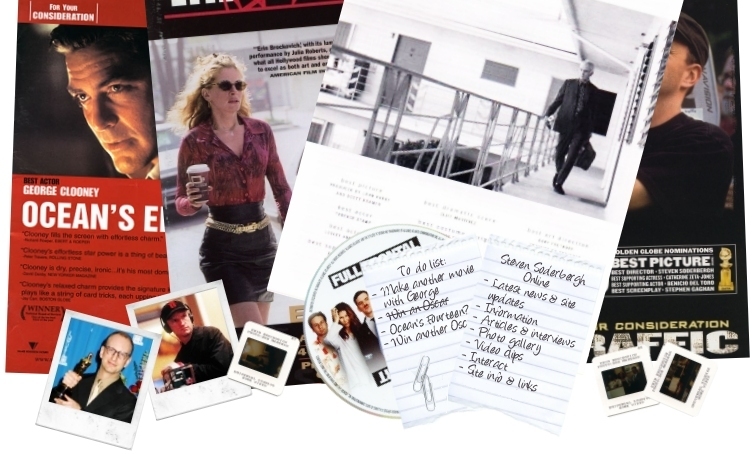

THE FANLISTING

There are 445 fans listed in the Steven Soderbergh fanlisting. If you're a Soderbergh fan, add your name to the list!

UPCOMING PROJECTS

LET THEM ALL TALK

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

KILL SWITCH

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

Now available from Amazon.com:

Haywire Haywire

Contagion Contagion

Now available from Amazon.co.uk:

Contagion Contagion

DVDs that include an audio commentary track from Steven:

Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection

Point Blank Point Blank

The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition) The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition)

The Third Man - Criterion Collection The Third Man - Criterion Collection

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

ADVERTS

|

|

|

|

Dialogue with Steven Soderbergh

By Gregg Kilday

(The Hollywood Reporter, July 30, 2002)

Since winning an Academy

Award last year for "Traffic" -- proving wrong the pundits who had

discounted his chances because he was competing against himself as the

director of "Erin Brockovich" -- filmmaker Steven Soderbergh has

barely taken a breath. He turned out the all-star caper movie "Ocean's

Eleven," a hit at Christmas, and has recently completed principal

photography on the metaphysical sci-fi tale "Solaris," starring

George Clooney, which 20th Century Fox will release Nov. 27. He also spent

18 days filming his latest movie, a low-budget experiment called "Full

Frontal," which Miramax Films opens Friday. Soderbergh intercuts a

cinema verite-esque look at seven denizens of Hollywood with a semiparody

of a glossy romantic comedy called "Rendezvous" to raise questions

-- if not necessarily to provide answers -- about current styles in

filmmaking. He spoke with The Hollywood Reporter's film editor, Gregg

Kilday.

The Hollywood Reporter: Winning an Oscar often has an inhibiting effect

on a filmmaker -- a director can spend years plotting his next move. How

did you avoid that?

Steven Soderbergh: I was actually scouting "Ocean's Eleven" before

we started shooting "Traffic," which was before the release of "Erin

Brockovich." By the time we were finishing "Traffic," Coleman

Hough and I were already working on the script for "Full Frontal,"

and I had written a first draft of "Solaris." Fortunately, there

was plenty going on to distract me. My long-term plan was always to take a

break after "Solaris."

THR: Were you drawn to "Full Frontal" because of the technical

exercise it offered or because of the story it tells?

Soderbergh: They're both bound in my mind because I wanted to make a

small, character-based film but not have it feel like the other small,

character-based films that I'd made. The form and the content in my mind

were both present at its inception, although ideas about both those things

shifted over the course of the writing and the shooting and the editing.

It ended up feeling very much like I wanted it to feel.

THR: So the notion of setting it in and around Los Angeles and

Hollywood was there from the beginning?

Soderbergh: Yeah, for practical reasons. My own apartment is in there at

the very end. My producer's house is David Hyde Pierce's house. Catherine

(Keener) drove my car; David Hyde Pierce drove one of my producer's cars.

It was the biggest student film you've ever seen.

THR: Why film the so-called "real-life" sections on video?

Soderbergh: I like the look of it when it's sort of not necessarily video.

I degraded it heavily in postproduction because I happen to like that

distressed quality -- I like the contrast, I like the grain, knowing that

I was going to juxtapose it with the (glossier) "Rendezvous"

footage. Had the movie been made entirely of DV footage, I probably

wouldn't have taken the distressing that far. But in the context of the

entire film, I felt like I could push it a little. I also liked the idea

of seeing name actors in that sort of aesthetic. I thought that might be

interesting.

THR: But the common wisdom in Hollywood is that you can't put name

actors like Julia Roberts in something so unglossy because their presence

conditions audiences to expect a bigger, slicker kind of movie.

Soderbergh: Well, we'll find out. That's the point, though. For 2 million

bucks, I think you can pose that question. I wouldn't do it for much more

that that, believe me. I think it is an open question to what extent

people can accept this kind of movie with these kinds of actors in it. But

again, I think it's worth finding out. If it doesn't work, then we know.

And if it does work, suddenly we might see more of these, which I don't

think is a bad thing.

THR: How'd you come up with an exploitation title like "Full Frontal"

for what is the antithesis of an exploitation film?

Soderbergh: Oh, that's just crass commercialism. There's nothing polite or

sophisticated about that. It was on the heels of having changed one title

("How to Survive a Hotel Room Fire") because it seemed less ironic

in the wake of Sept. 11 and then changing the next title ("The Art of

Negotiating a Turn") because (Miramax co-chairman) Harvey (Weinstein)

said it was the worst title he had ever heard in his life. So the third

one was the result of my sitting down and trying to think of a title that

would make Harvey evaporate in a state of ecstasy. That was the best I

could do. He was pretty happy. He didn't evaporate, but he was

oscillating.

THR: The movie is asking whether low-budget, indie-looking films are

more "real" than Hollywood movies? How do you answer that question?

Soderbergh: You can say it poses that question, or you can say I'm

satirizing independent movies in the same way I'm satirizing the meet-cute

in a comedy like "Rendezvous." But at the end of the day, I was

really trying to remind people -- whether they need to be reminded or not

-- they are both constructs, and they are both, depending on the material

you are trying to put across, legitimate. "Full Frontal" was

actually a useful way to work through some of these issues of cinematic

veracity so that I could get my head clear enough to make "Solaris"

without sitting around and pondering these sorts of cinematic questions.

I'm interested in what the contract is between audience and the film and

the filmmaker and how far can you push that. If there's a contract between

the audience and the film, I was sort of exploring the fine print with "Full

Frontal."

THR: Ultimately, you remind the audience that it's only a movie.

Soderbergh: I certainly didn't mean it as a "fuck you." To my mind, it

doesn't negate having had some emotional connection, if you have, with any

of those characters. If you were moved by the scene with Catherine Keener

and David Hyde Pierce, I'm not saying you shouldn't have been.

THR: George Lucas has been urging his fellow directors to give up film

for high-definition video. Are you ready to follow his lead?

Soderbergh: My own attitude is that film as a capture medium isn't going

anywhere, and it shouldn't be going anywhere. I'm much more a proponent of

digital projection. I think video as a capture medium is really

interesting, and I plan to explore it more myself. But film as a recording

medium is pretty hard to beat. It's really beautiful. It does some

wonderful things that are specific to the photo-chemical world. Doing your

shooting on film and having digital projection is sort of the ideal.

THR: Given that this film is an experiment, how will you judge its

success?

Soderbergh: I probably won't for a while. I really think it's something

that later in context -- if I feel like it -- I will sit down and think

what did I do right, what did I do wrong? But I usually wait a long time

to do that because in the hothouse atmosphere of making and selling a

movie, I think it's really, really difficult to judge what you've done.

THR: You may have to decide by the time you do the DVD commentary.

Soderbergh: I know, it's frustrating. I found it really difficult on the "Traffic"

DVD. I wish we could have waited longer to determine if it was something

worthy of a commentary because I don't know if every movie is. I certainly

know that every movie of mine isn't. You feel like you're anointing it

before the jury's in. It was actually easier (to do the commentary for) "Ocean's

Eleven," which isn't about anything. You feel like you can talk about

it without being pretentious. This one will be fun, I think. We have a lot

of material and extra stuff. I imagine that in the spirit of the movie, it

will be sort of funky and pleasantly interactive.

THR: Moving on to your other interests. What's the status of the

directors company that you've been discussing with David Fincher,

Alexander Payne and Spike Jonze?

Soderbergh: We're still working on it. Until it happens, I feel like

there's nothing to talk about. It would have been our preference for this

to come out once it was done, and it's not done. There's just nothing

concrete to discuss.

THR: How about Section 8 (the production company in which Soderbergh is

partnered with Clooney)? With such movies as "Welcome to Collinwood"

and "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind" nearing release, do you see a

company profile developing?

Soderbergh: I've made a concerted effort to be really involved with all

the projects that we've got going. But we've just done whatever interests

us. It will be as eclectic as the choices that George and I have made

historically. We're really open to any kind of subject matter, and we're

primarily director-driven.

THR: So are you determined to stick by your plan to take a year off

from filming once "Solaris" is complete?

Soderbergh: Directing a movie takes an enormous amount of mental space.

This is the first time I've been editing and not in preproduction on

another movie, and it feels really, really nice. I feel lazy in a way. I

think dropping off the grid for an actor is probably a riskier notion than

it is for a director. I don't think anybody cares if a director stops

working for a year. For me, it's just a necessary thing; it's

self-preservation. I need time to recharge.

THR: To end on a frivolous note. In the "Full Frontal" scene

where David Duchovny has a massage, there's an obvious, telltale prop that

probably would have required weeks worth of negotiations on a studio

feature.

Soderbergh: (Laughing). I think the consensus was to go for an

average-size prop and one that wasn't electrified. I think we spent more

time talking about that because we were very concerned that David would

hurt himself. On paper, it's a very long scene, and I cut a considerable

amount off the head of it, no pun intended. And I was shooting all these

things in single, uninterrupted takes, and we would get five minutes into

a take, and he would roll over and readjust and we'd pan over. Whether or

not David had adjusted the prop in a way that I thought was correct, I

didn't know until I panned over five minutes into the take. So there were

a handful of takes where everything would go perfectly, and I'd pan over

and go, "Nah, that penis looks wrong." I think David got a kick out of the

absurdity of it. If people are laboring under the delusion that a bunch of

sophisticated people were making the movie, I'd appreciate it if you'd set

the record straight. It's worse than they imagine.

|

|