|

|

CALENDAR

8th February: Side Effects released (US)

15th March: Side Effects released (UK)

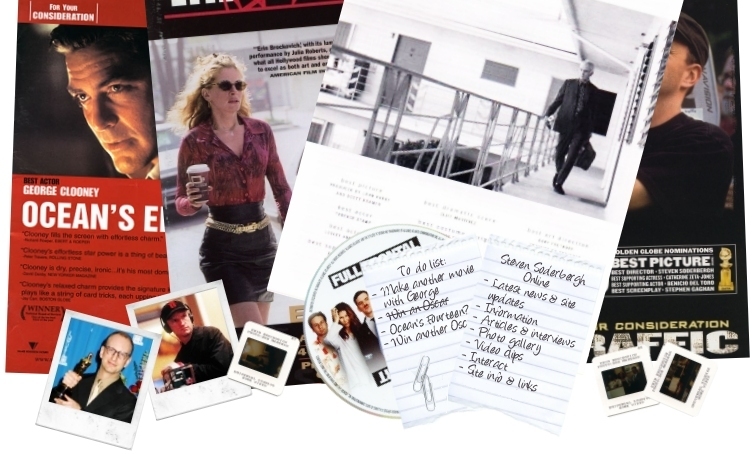

THE FANLISTING

There are 445 fans listed in the Steven Soderbergh fanlisting. If you're a Soderbergh fan, add your name to the list!

UPCOMING PROJECTS

LET THEM ALL TALK

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

KILL SWITCH

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

Now available from Amazon.com:

Haywire Haywire

Contagion Contagion

Now available from Amazon.co.uk:

Contagion Contagion

DVDs that include an audio commentary track from Steven:

Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection

Point Blank Point Blank

The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition) The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition)

The Third Man - Criterion Collection The Third Man - Criterion Collection

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

ADVERTS

|

|

|

|

Hollywood is making intelligent movies again, thanks to

Steven Soderbergh,

a modern-day Hitchcock who brings the best out in everyone

(The Sunday Times, August 25, 2002) A cursory glance at the films

on release this summer in America is enough to make any cinephile head for

the video shop in search of more challenging viewing. Movies made by

committee seem to be the order of the day, with sequels such as Men

in Black 2 and Goldmember mixed in with prequels like

Attack of the Clones and films like XXX

that the studios hope will spawn the franchises of the future. On the face

of it, there's plenty of evidence to suggest the pessimists of the late

1970s were right when they predicted that the global success of Star

Wars and Jaws would result in a Hollywood dominated by

so-called "event" movies. But if that's the case, then where do

film-makers such as Christopher Nolan, Steven Soderbergh, David Fincher,

Sam Mendes and Curtis Hanson fit in?

All of the above work within the same studio system that turns out the

dross that's currently clogging up our multiplexes, but they specialise in

making films that are thought-provoking and reliant on storytelling rather

than special effects. Not only that, but they're successful as well. It's

no wonder that the likes of Julia Roberts, George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Ed

Norton, Tom Hanks and Al Pacino are queuing up to work with these

directors and often at a fraction of their normal fees.

It's a situation that didn't exist 10 years ago, when movies were still

categorised as either art-house or mainstream and a thriving independent

film sector was actively challenging the dominance of the studios. The

initial reaction of the studios was to absorb the more successful indie

companies, such as Miramax and New Line, or to set up boutique operations

of their own, such as Fox Searchlight, to release low-to medium-budget

films with more adult themes than their seasonal blockbuster fare. Now

even that distinction is breaking down, with movies like American

Beauty and Fight Club - by far the most radical film

to emerge from Hollywood in recent years - being produced by the main arms

of the studios. All of which raises the tantalising prospect of a return

to the golden age of the 1940s, when the likes of Alfred Hitchcock,

Preston Sturges, Billy Wilder and, for a while, Orson Welles worked within

the studio system to create some of the all-time great films, most of them

still featuring in today's polls of audiences' top 100 films.

The key figure in this new group of studio-based auteurs is the

39-year-old Steven Soderbergh. With his phenomenal work-rate - in the past

two years he's turned out Erin Brockovich, Traffic,

Ocean's Eleven and now Full Frontal - and

impeccable credentials as the director of sex, lies and

videotape, the film that kick-started the independent movie boom of

the late 1980s and early 1990s, he's become an enormously influential, if

low-key, presence in Hollywood. It was Soderbergh that Christopher Nolan,

the British director whose tricky thriller Memento was the sleeper

success of last year, turned to when he was trying to set up Insomnia,

his follow-up. "Steven was instrumental in introducing me to the studio,"

recalls Nolan. "They took me seriously because he asked them to."

Soderbergh then agreed to executive produce Insomnia via Section

Eight, the production company he set up with George Clooney in 2000. It's

not the only time he's helped out a British director. When Ken Loach came

to LA in 1999 to make Bread and Roses, his only

US-set film, it was Soderbergh who helped him find a crew and sponsored

him for his Directors Guild card.

Soderbergh's collaboration with Clooney revitalised a career that, after

the success of the Palme d'Or- winning sex, lies and

videotape, had nosedived with a string of obscure and unsuccessful

films. They first worked together on 1998's Out of Sight,

and, as he subsequently did with Julia Roberts in Erin

Brockovich, Soderbergh demonstrated then that he has the knack of

getting the best out of his actors.

"If I do one thing well, I think it's that I have an instinct for what an

actor's strengths are and I know how to play to them," Soderbergh once

told me. "I know how to construct an environment and a sequence that will

play to what they play well." Not only that, but he and Clooney share a

similar taste in material that's both accessible and intelligent, which

are the qualities that used to define the best of the movies that came out

of the studio system. "When I look at what I consider to be the great

films of the past, like any of Hitchcock's, a lot of them are like that,"

says Nolan. "I mean, Citizen Kane was a studio movie." He

sees his own work as falling into that category too. "I always thought

Memento was a very mainstream movie. I never saw it as an art film,

and I felt that at every stage everyone underestimated how many people

would respond to it."

With Insomnia, which is a remake of a 1997 Norwegian thriller about

a sleep-deprived detective on the trail of a brutal murderer, only

transposed to the permanent light of the Alaskan summer, Nolan says he was

consciously trying to revisit the era that gave us classic movies like

Double Indemnity and Notorious. "My interest in remaking

the film was to make it as the kind of Hollywood morality tale, the kind

of cop drama that studios used to be really good at making 50 years ago. I

wanted to create a sympathetic protagonist who would be the iconic cop

figure of American movies, but with a slightly more modern underpinning. I

mean, we do go into some very murky waters."

With Al Pacino, who's certainly an icon, and a surprisingly effective

Robin Williams as his nemesis, Insomnia doesn't pander to audiences

by offering them the traditional resolution such stories tend to have. "To

me, what's important is the idea of redemption," points out Nolan. "That's

the way these studio movies were always deceptive in the past, because

they weren't so much about punishment as redemption." Audiences seem to

have responded to this more complex model because Insomnia has

taken $ 70m at the US box office so far and is still performing strongly,

despite having to compete for screens with the summer blockbusters. In

doing so, it's following in the recent footsteps of similarly challenging

movies, such as Traffic, LA Confidential, Three

Kings and Fargo.

Not that Soderbergh seems too bothered by whether the films produced by

Section Eight, or indeed his own, do well in a commercial sense. "I'm not

a result-oriented person," he says with a smile. "I'm a process-orientated

person, so when one process ends, I look to the next process. The result

is interesting to me and makes for good parlour conversation, but I can't

control it." That's heresy in LA, where studio executives spend their

Friday nights driving from one multiplex to another to check out the size

of the queues for their latest offerings. But there's also a growing

awareness in Hollywood that not every cinema-goer is a 15-year-old who

wants a big bang in return for his nine bucks. Then there's the fact that

the stars are well aware that they don't win Oscars for appearing in the

likes of MiB2. Perhaps Tom Cruise has signed up for Mission:

Impossible 3 because David Fincher is directing it.

However, it's often foreign film-makers who prove to be the best at making

superior American movies. Nolan and Sam Mendes are just the latest Brits

who've jumped to the top of studios' wishlists, but Hollywood now looks

further afield than Europe. Ang Lee, who's shooting The

Incredible Hulk, and Shekhar Kapur, who's just finished the

umpteenth remake of The Four Feathers, lead the Asian

charge, while the Mexican Alfonso Cuaron is following the exuberant Y

tu mama tambien by directing the third Harry Potter film.

Nolan believes that it's entirely natural that he and the rest of the

foreign legion should be taking on such projects. "I don't think Hollywood

belongs to America, I think it's a universal language that just happens to

have an American accent. The people who make the films have always come

from all over the world."

Perhaps because he's half-English and half-American, he's never subscribed

to any nationalist theories of cinema. "In England there's a very false

notion of trying to assert national character in film-making, and I think

that can't be productive. It means that you're being told that you should

tell a particular kind of story, which is an utterly false premise from

which to embark on a film- making process," he notes. "Hollywood asserts

only business as a national characteristic - that has to underpin

everything that gets made in the studio system, and in a weird way I think

that's more honest."

As for Soderbergh, he's still working at a rate that leaves every other

current director in the dust. With the sly and rather too self-referential

Full Frontal, which he wrote while making Ocean's

Eleven and shot in a mere 18 days, already out in America, he's busy

finishing off his remake of Solaris, the Tarkovsky sci fi classic.

That's in addition to his producing duties on George Clooney's directorial

debut, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, and

Welcome to Collinwood, a crime caper that will be the

next Section Eight film to hit our cinemas. "I think it's good to be busy,

because it keeps you from being precious about the movies," he says.

"There's a healthy, dispassionate viewpoint that comes from moving quickly

and knowing that once I'm finished I'm going to do something else. You

make decisions based on instinct, and you don't agonise over stuff." And,

of course, that's exactly what the best directors used to do back in the

heyday of the studio system.

|

|