|

|

||||||

|

|

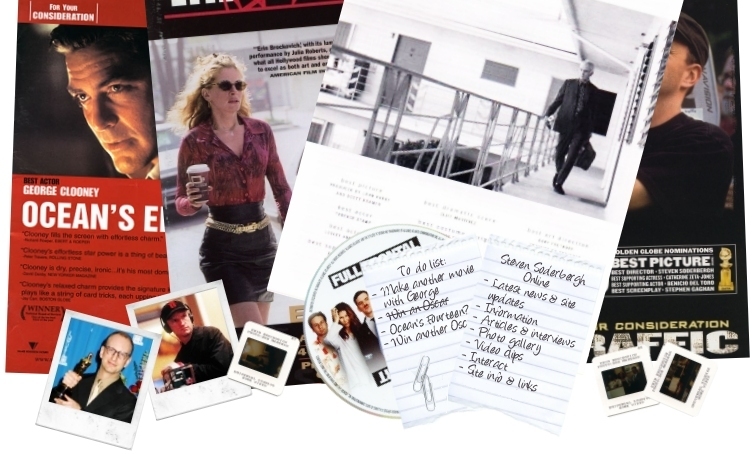

CALENDAR

THE FANLISTING

UPCOMING PROJECTS

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

ADVERTS

|

French New Wave Influences in Steven Soderbergh Films "Godard is a constant source of inspiration. Before I do anything, I go back and look at as many of his films as I can, as a reminder of what’s possible."-Steven Soderbergh Academy Award winning director Steven Soderbergh has directed over twelve films. From his critically acclaimed debut, sex, lies, and videotape, Oscar winner Traffic, to box office hit, Ocean's Eleven. While his films cover a variety of different subject matter, his directorial style remains somewhat constant. Much of his style seems to stem from his fascination with the French New Wave movement. His utilizing of Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows freeze frame is evident in the narrative structure of the 1998 film Out of Sight while his use of color themes in Traffic seems to harken back to the opening scene of Jean-Luc Godard's Contempt. Furthermore, many of Soderbergh's films incorporate breaks in the 180 degree line, jump cuts, direct address, and an all out attack on conventional Hollywood cinema. It becomes clear, when looking at the films in Soderbergh’s filmography, that much of his directorial style lies within the roots of the French New Wave. In order to look at Soderbergh’s French New Wave roots, the roots of the French New Wave must first be noted. The beginning of the French New Wave can be traced as far back as 1955 with the production of Jean-Pierre Melville’s noir Bob le Flambeur. However, it was not until the 1959 when Francois Truffaut screened his autobiographical film The 400 Blows at Cannes that the French New Wave officially took hold. The filmmakers of the French New Wave revolted against what was considered classical French cinema and praised the conventions of commercial Hollywood cinema because of the embracing of film auteurs like Hitchcock and Hawks. Furthermore, as seen in Godard’s 1960 film Breathless, the New Wave challenged the "polished French cinema of quality" with what was considered a casual look (Bordwell Thompson, 420). Cinematography was also influenced by the New Wave. Movement became increasingly common with the utilization of panning and tracking shots to the use of hand-held cameras. While the movement seemed to end in 1964, it gave rise to a simular movement of the popular independent Hollywood film which went against the conventions set forth by Hollywood. Soderbergh was one of the founding members with his 1989 debut film, sex, lies, and videotape. With the exception of some of the long takes and the reflexive role of the camera in sex, lies, and videotape, the influence of the French New Wave in Soderbergh’s early films seems pale in comparison with the films that graced the middle of his on going career. It was not until 1996 when Soderbergh produced Gray’s Anatomy and Schizopolis that the New Wave’s influence seemed to take on full potency. As seen in his published journals, dating from the post-production of both films in early 1996 to pre-production of Out of Sight in early 1997, Soderbergh became increasingly upset with the Hollywood system and ventured into guerrilla filmmaking. His first film to become a product of this hiatus, Gray’s Anatomy, consisted entirely of an eighty minute monologue by Spalding Gray regarding problems with his eye sight. In the film, Soderbergh utilized one of the characteristics of the New Wave movement: direct address. Conventional Hollywood cinema criticizes an actor who looks at the camera. The response to direct address is even more looked down upon. However, by allowing Gray to address the camera, Soderbergh created less of a barrier between the audience and the subject, thus making the film more personal. Soderbergh’s second film of 1996, Schizopolis, exemplified further the French New Wave influence on his films. Jump cuts are increasingly common, giving the film what is commonly considered a "sloppy" feel. In the interrogation scene of the paranoid-schizophrenic exterminator, Elmo Oxygen, Soderbergh utilizes this visual technique numerous times to provide a temporal ellipsis. Visual style aside, Soderbergh also adds unconventional narrative techniques to the film. For example, during the film’s self-proclaimed third act, Fletcher Munson (Soderbergh) and his wife (Soderbergh’s wife at the time, Betsy Brantley) experience comical marital dispute and lack personal communication. Soderbergh, aside from making this obvious in his performance and Brantley’s, makes this breakdown of communication literal by having his character speak various foreign languages while his wife speaks English. This, of course, is not a technique commonly seen or embraced in conventional Hollywood cinema. However, casual humor is a characteristic commonly found in New Wave films. For example, a variation of this technique is seen in Godard’s Band Of Outsiders when all three main characters resolve to be silent for a moment and Godard literally makes the scene mute of all sound. Soderbergh’s return to Hollywood in 1997 brought forth one of his most acclaimed films, the adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s noir Out of Sight. The film was nominated for numerous Academy Awards, including one for Anne V. Coates for best editing. It is the editorial techniques in Out of Sight that showcase much of the characteristics of the French New Wave. One of the most evident visual traits of the film is Soderbergh’s continual use of freeze frames. As previously noted, this first appeared in the final shot of Traffaut’s The 400 Blows. While Traffaut used his freeze frame to give the film an ambiguous ending, Soderbergh utilizes his temporally to lend the film a stream of consciousness effect. For example, when Jack (George Clooney) and Buddy (Ving Rhames) are left behind by Glen after the jail break, Soderbergh flashes back to one of the first instances in which the duo met Glen. Time does, however, catch up with itself. This occurs as the window between past and future narrows during the cross cutting of the scenes in the bar and Karen’s hotel room. As Jack and Karen are making love and are preparing to make love, the freeze frames become increasingly common until the two events occur within the same moment. This leads to the final freeze frame of the film and a fade to black, separating the past from what has become the present. Soderbergh’s follow up, 1999’s The Limey, also incorporated an editorial technique common in French New Wave films: discontinuity editing. Most notably evident in the opening scene of Godard’s Breathless, this technique makes the viewer confused to the character’s spatial relationship to their surroundings. Most of this confusion stems from the lack of an establishing shot and frequent breaks across the 180 degree line. These traits are seen numerous times in The Limey. The best example, however, is during the Wilson’s (Terence Stamp) monologue to Elaine (Lesley Ann Warren). Soderbergh shoots this exchange in numerous settings ranging from a restaurant, a boardwalk, to a hotel room and intercuts them together. By doing so and not altering the audio track to include an ellipsis, Soderbergh not only makes the audience unsure of where the true conversation took place but disorientates them. The utilization of this technique also visually encourages the audience to question the point of view and information they are being given in the narrative. The following year not only brought Soderbergh the major success of his two latest films, Erin Brockovich and Traffic, but an Academy Award nomination for the former and a win for the later. Traffic became the perfect hybrid of Soderbergh’s Hollywood and guerrilla filmmaking. Like his previous films, much of the style Soderbergh displays on Traffic seems to stem from his fascination with the French New Wave. The most notable of the two techniques is that of the color themes for each of the locales the film takes place in. Mexico is basked in a washed out yellow while Ohio is left to soak in cold blue tones, giving the audience a visual reference to each location. This technique, while utilized in a different context, seems to be taken from the opening scene in Godard’s Contempt. Contempt, Godard’s first venture into the realm of French film industry, is notable for its unconventional use of cinescope and technicolor. The first scene is accentuated with the extremely reflexive movement of changing colored filters on one take, making the scene go from a dark red, yellow, to dark blue while the audience watches the filters change over the camera lens. The second, most notable, French New Wave property exemplified in Traffic is Soderbergh’s use of the hand-held camera. This technique was utilized in both Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Godard’s Breathless in order to allow the audience to explore space. Soderbergh does the same but adds the common feeling of un-balance to these shots. For example, while pursuing Helena (Catherine Zeta-Jones) through the streets of Tijuana, Soderbergh lets the camera jitter. This gives the audience a feeling of realism by visually not allowing a person’s walk to appear perfectly smooth like a stedicam would. Following his success with Traffic, Soderbergh brought audiences the big budgeted remake of the Rat Pack film, Ocean’s Eleven. Starring George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Matt Damon, and Julia Roberts, Ocean’s Eleven also became Soderbergh’s most successful and most conventional film. However, even his most conventional film was not untouched by the New Wave. For example, Livingston Dell’s (Edward Jemison) frustrating encounter with the casino’s computer is graced with jump cuts to ellipse time. Furthermore, direct address and the reflexive technique of coming into focus are utilized when Rusty approaches towards the camera dressed as a doctor. However, Soderbergh’s next feature, Full Frontal, would prove to be a full reversal on Ocean’s Eleven. Supplementing all copies of the screenplay to Full Frontal, Soderbergh authored his infamous list of rules for the stars demanding everything from personally driving themselves to the set, picking and providing their own wardrobe, maintaining their own hair and make-up, not allowing trailers or personal free time, and encouraging improvisation. Furthermore, the film was to be shot on digital video handicams with a shooting schedule only lasting eighteen days. This film was clearly not going to be what was considered conventional Hollywood cinema. Soderbergh, in the commentary on the recently released DVD, compares the film to the work of Godard and the French New Wave and this can clearly be seen in the film. From the use of direct address, soft focus, jump cuts, and other examples of discontinuity editing, Full Frontal embodies the very essence of the French New Wave and it is clear, looking through Soderbergh’s filmography, that this historical film movement touches almost every one of his films. Works Cited Contributed to StevenSoderbergh.net by Drew Morton

|

||||

|

Steven Soderbergh Online is an unofficial fan site and is not in any way affiliated with or endorsed by Mr. Soderbergh or any other person, company or studio connected to Mr. Soderbergh. All copyrighted material is the property of it's respective owners. The use of any of this material is intended for non-profit, entertainment-only purposes. No copyright infringement is intended. Original content and layout is © Steven Soderbergh Online 2001 - date and should not be used without permission. Please read the full disclaimer and email me with any questions. |

||||||