|

|

CALENDAR

8th February: Side Effects released (US)

15th March: Side Effects released (UK)

THE FANLISTING

There are 445 fans listed in the Steven Soderbergh fanlisting. If you're a Soderbergh fan, add your name to the list!

UPCOMING PROJECTS

LET THEM ALL TALK

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

KILL SWITCH

Information | Photos | Official website

Released: 2020

ADVERTS

NEW & UPCOMING DVDS

Now available from Amazon.com:

Haywire Haywire

Contagion Contagion

Now available from Amazon.co.uk:

Contagion Contagion

DVDs that include an audio commentary track from Steven:

Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection Clean, Shaven - Criterion Collection

Point Blank Point Blank

The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition) The Graduate (40th Anniversary Collector's Edition)

The Third Man - Criterion Collection The Third Man - Criterion Collection

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

ADVERTS

|

|

|

|

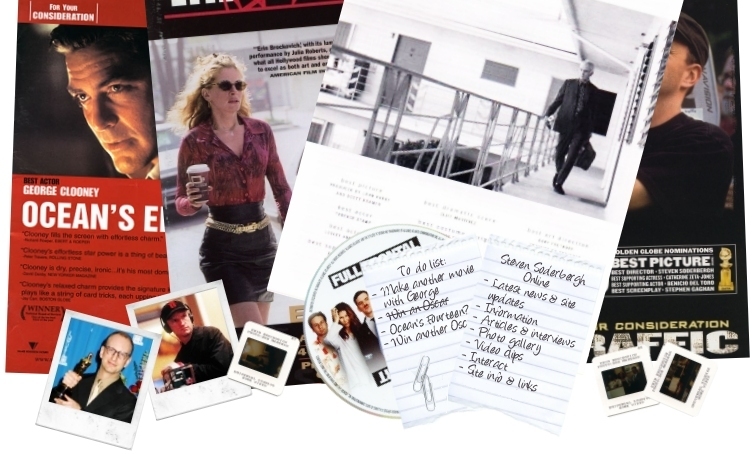

Power behind the screen

In partnership with George Clooney, director Steven Soderbergh has become

one of Hollywood's top players. David Gritten meets him.

By David Gritten

(The Daily Telegraph, February 8, 2003) Being

acclaimed as a boy wonder in the arts can be something of as albatross. How do

you ever recapture that sense of gilded, gifted youth? What do you do for the

rest of your life? Steven Soderbergh joined the boy wonder club in 1989 by

winning the Palme d'Or at Cannes with his debut film, Sex, Lies and Videotape.

He was just 26, and acknowledged the problem even as he accepted the award: "I

guess it's all downhill from here," he said.

For almost 10 years his prediction seemed spot-on. Critics grudgingly respected

his next films (Kafka, King of the Hill, The Underneath, Gray's Anatomy

and Schizopolis) but audiences stayed away. Even Soderbergh wasn't

surprised: "When I look at The Underneath now, it's just so

sleepy," he tells me. "It was a broken-backed idea to begin with. There should

be some cultural police force that arrives when you say: 'I want to make an

armoured car heist movie but have it be like (Antonioni's) Red Desert.'

Someone should chain you up and carry you off.

"But I learned a lot from making that film, if only that I needed to change

course. It was the first time I'd been on a film set and wondered whether I

wanted to continue. I was in danger of becoming a formalist." His turning point

came in 1998 with Out of Sight, a stylish, funny, romantic

thriller that significantly marked his first collaboration with leading man

George Clooney. It was a big hit, and Soderbergh admits: "The experience

loosened me up a lot. It was based on a script that was already written. It was

my first film that wasn't all about me."

With Out of Sight, Soderbergh found his niche. He now

operates within Hollywood like a loyal opposition, making genre films with a

grace and flair that eludes most directors employed by studios. He is not above

a trivial caper movie like Ocean's Eleven, but invests it with such elan

that it becomes pure pleasure to watch. In lesser hands, Erin

Brockovich would be a routine true-story TV movie; but Julia Roberts's

performance won her an Oscar, and the film was nominated for four more. That

same year, 2000, was Soderbergh's annus mirabilis; his film Traffic,

about the drugs war in America and Mexico, won four Oscars. He was back.

At 40, he has gathered around him an informal repertory company. It helps that

they include some of Hollywood's biggest names: Clooney, Roberts, Brad Pitt.

Intriguingly, Soderbergh uses them strictly for specific, even small, roles

rather than casting them for star value.

He now wields subtle but huge influence in Hollywood. In 2000 he and Clooney

formed Section Eight, a small production company with a plain philosophy: "If we

can be lean and mean, get some interesting movies made and work with really good

film-makers, it's worth doing."

Section Eight (it's a US military term, meaning a discharge for physical or

mental unfitness for service) is based at Warner Bros, and already making its

presence felt. Two of its films have opened in America: Confessions of a

Dangerous Mind, based on the memoirs of eccentric TV game-show host Chuck

Barris, directed by and starring Clooney; and Welcome to Collinwood, a

comic remake of the burglary caper film Big Deal on Madonna Street, with

Clooney in a minor role.

I spoke twice to Soderbergh about his recent work and Section Eight - first at

the Venice Film Festival, then recently over informal drinks one evening in

London. He is good company: witty and gossipy about Hollywood, and occasionally

forthright about other film-makers.

He now commands such respect that he is one of few directors who can be equally

candid with studio bosses. He and Clooney were executive producers of

Insomnia, Al Pacino's recent hit, but Warner Bros fretted about the young

Englishman Christopher Nolan directing it. "I went in and told them, look, Chris

will deliver the film on time and on budget," Soderbergh recalls. "And he'll

give you an interesting movie too. You'd be fools not to hire him."

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind was made for Miramax, whose boss, the

notoriously volatile Harvey Weinstein, was nagging a stubborn Clooney to cut the

film by a few minutes. "I told Harvey, 'Look, I think you'd want to be in the

George Clooney business for a few years. But right now he's so pissed off he

never wants to work with you again. Where's the sense in that?' I think I got

him to back off a little."

Fellow directors mention small acts of encouragement and support that seal their

admiration for Soderbergh. Section Eight were also executive producers of Todd

Haynes's acclaimed new film Far from Heaven; Haynes told me

Soderbergh "helped navigate us through some points of budgetary tension. More

than once, he offered to help us cover some overspending out of his own pocket.

He was just there for us." And when Britain's Ken Loach was in Los Angeles

making his modestly-budgeted Bread and Roses, about

striking office workers, Soderbergh (who greatly admires Loach) volunteered to

find him a local crew for the low-paying shoot.

None of this virtue or influence makes Soderbergh immune to box-office failure.

In America, he has had two recently. Critics panned the experimental Full

Frontal, a self-indulgent film with an insider's view of Hollywood types;

it was shot in 18 days for just $2 million. "Columnists attacked me on the

leader pages," he sighs. "You'd think I was a serial killer. If it had cost more

than $2 million, I'd be worried. But I wanted to make something that wasn't

immediately digestible, which was partly why I made it cheaply."

He made his latest film, Solaris, for Fox at a far higher price. A

radically different version of Tarkovsky's 1972 classic, it stars Clooney as a

psychologist in space, visiting a space station where astronauts' dormant

memories are revived; in his case, this brings him face to face with his wife

(or a semblance of her) who he knows committed suicide. It is a film of great

fluency and beauty, and may be Clooney's best performance yet. But American

critics helped bury Solaris at the box-office; it does not conform to

Hollywood ideas of a neatly resolved story or a happy ending.

Yet he is quick to defend his film, and his lead actor: "Solaris is

unlike anything George has done. I benefited from him having just directed a

movie. He was tired, and open to doing things he might not have been a year

before. There are abstract emotions in this movie, hallucinogenic fever dream

sequences where he thinks he's in the moment of his own death. That was

difficult for George to portray with a camera four feet from his nose."

As for the commercial failure of Solaris, Soderbergh is insouciant: "I'd

rather it was a real flop than just a minor hit. I'm fine about it. It only cost

Fox £30 million. They'll make it back on video and DVD eventually."

He says that, yet in the next breath complains about Hollywood's waste and

excess: "I hate it. It drives me nuts. That's what bothers me about the place.

That it's driven by money is no surprise. But I hate the indulgence it provokes

in people. It's tied into the films they make now. If you make a $50 million

movie that should cost $30 million, it won't be as interesting. The pressure to

be appreciated by a mass audience has a real impact on the quality of films

now."

Few people working within Hollywood state that case so baldly, and his candour

raises the question of who might follow in his footsteps. He plans to take

several months off to spend time with the creative team behind the hit

television series The Sopranos, and write a book about the programme. He

admires two young American directors, Wes Anderson and Paul Thomas Anderson, but

cautions: "It's time they grew up a little. They need to start making films

about things more than 10 feet from their nose."

Could that be the boy wonder experiencing the onset of middle age?

|

|